A stent is a small, mesh-like tube placed inside an artery to keep it open after angioplasty. It is commonly used in the treatment of coronary artery disease, where narrowed vessels restrict blood flow to the heart muscle.

Drug-eluting stents release medication to prevent re-narrowing, while bare-metal stents provide structural support without medication. The choice depends on patient-specific factors, including risk of restenosis and medication tolerance.

The procedure involves guiding the stent into place via a catheter inserted through the femoral or radial artery. Balloon expansion secures the stent, ensuring improved blood flow and reduced chest pain or ischemic events.

Post-stent care requires dual antiplatelet therapy to prevent clot formation. Regular follow-up, lifestyle changes, and management of cardiovascular risk factors are essential for long-term success and prevention of complications.

| Medical Name | Stent Application (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) |

| Frequent Use Areas | – Coronary artery disease (heart vessel blockages)- Peripheral vascular diseases- Kidney, brain, biliary tract blockages |

| Causes | – Vascular occlusion or narrowing – Acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) – Chronic ischemic diseases |

| Risk Factors | – Hypertension- High cholesterol- Diabetes- Smoking- Advanced age |

| Complications | – Re-narrowing within the stent (restenosis)- Bleeding- Vessel rupture or dissection- Blood clot formation (stent thrombosis) |

| Diagnostic Methods | – Angiography – Doppler ultrasound (for peripheral vessels) – Computed tomography angiography (CT angiography) |

| Treatment Methods | – Post-stent antiplatelet drugs (blood thinners)- Lifestyle changes- Regular follow-up and control |

| Prevention Methods | – Healthy diet- Regular exercise- Quitting smoking and alcohol use- Blood pressure and cholesterol control |

What is a stent and how does it work?

To better understand scaffolding, imagine a tunnel that is about to collapse. A strong scaffold placed inside the tunnel supports the walls of the tunnel, preventing it from collapsing and allowing traffic to flow safely. A stent does the same inside a blood vessel. When placed in an area narrowed by atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), it acts like a scaffold, widening the artery and keeping it permanently open. This removes the obstacle to blood and therefore oxygen reaching the tissues and organs.

Stents are not uniform devices. They are made of different materials depending on their intended use and purpose. These materials determine both the durability of the stent and its compatibility with the body. Various high-tech materials are used in the production of stents used today.

The main stent materials used are as follows:

- Stainless steel

- Cobalt-chromium alloys

- Platinum-chromium alloys

- Poly-L-lactic acid (in fusible stents)

- Magnesium alloys (for fusible stents)

- Silicone (in respiratory stents)

- Polyester fabric (in stent-grafts for aortic vessels)

Of these materials, cobalt-chromium and platinum-chromium alloys are the basis of today’s modern heart stents, as they are both very strong and can be manufactured with very thin wires. Thinner wires make the stent more flexible, allowing it to reach even the most convoluted parts of the vessel and causing less damage to the vessel wall. This speeds up the healing process and increases long-term success.

What is an angio stent and in which cases should it be implanted?

The commonly used term “angio stent” actually refers to a stent placement procedure. This procedure is usually performed as a follow-up to a diagnostic procedure called “coronary angiography”. When stenoses in the vessels are clearly detected during angiography, if the stenosis is critical, it can be treated with a stent in the same session. In other words, “angio stent” is a combined treatment process in which the problem detected by angiography is solved with a stent.

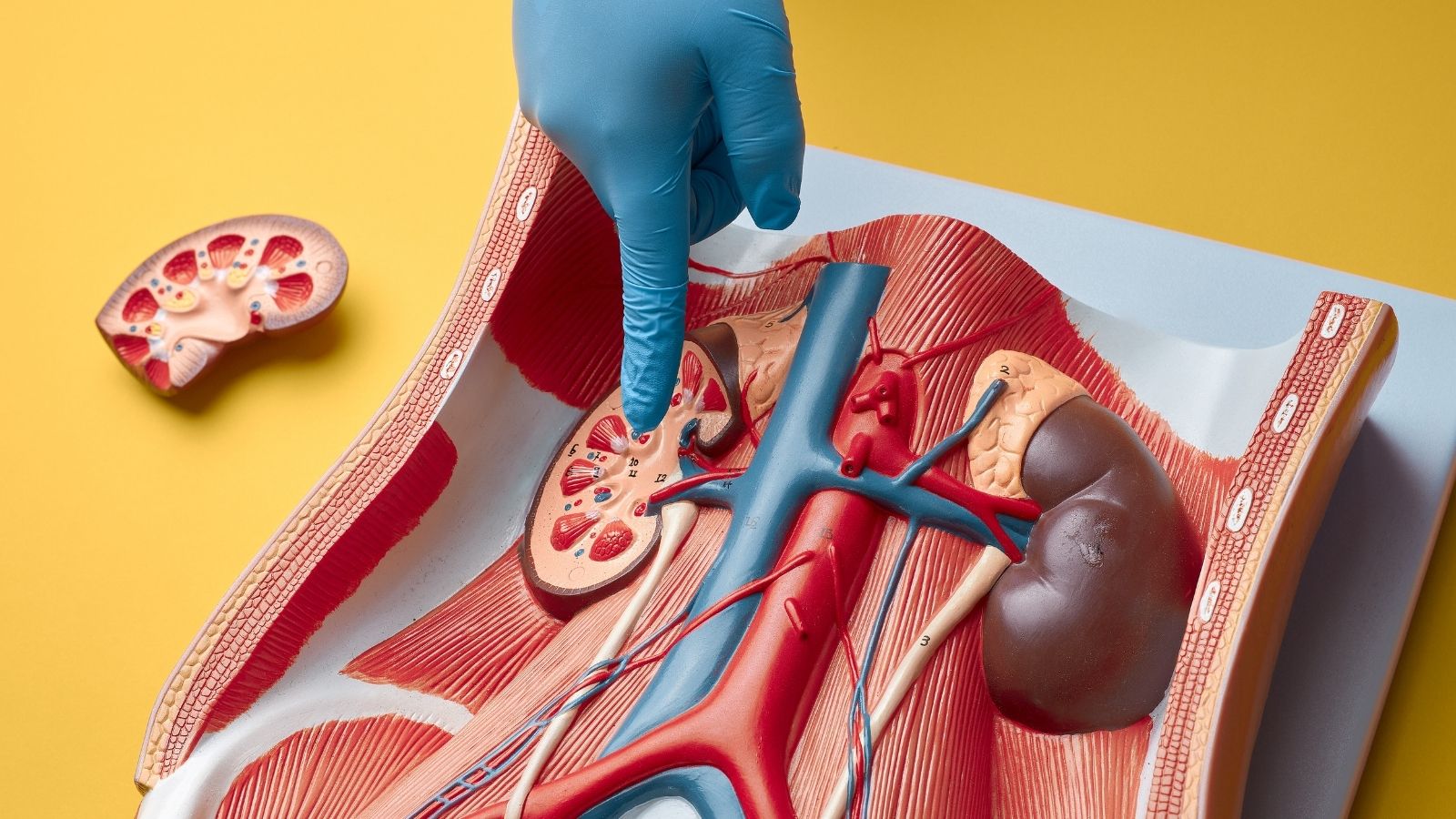

Stenting plays a life-saving or life-enhancing role in many different vascular problems in the body. It is not a technology limited to heart vessels.

The main conditions that require stent implantation are as follows:

- Coronary Artery Disease

- Carotid Artery Disease (Carotid Artery Occlusion)

- Peripheral Arterial Disease (Leg and Arm Vascular Blockages)

- Aortic Aneurysms (Vascular Ballooning)

- Renal Artery Stenosis (Kidney Stenosis)

- Bile Tract Obstructions

- Ureteral (Urinary Duct) Stenosis

- Respiratory Tract Stenosis

The most common of these conditions is undoubtedly Coronary Artery Disease. This disease, which is caused by narrowing or blockage of the arteries supplying the heart, is the main cause of chest pain (angina) and heart attack. During a heart attack, the rapid opening of the blocked artery with a balloon or stent prevents permanent damage to the heart muscle and saves the patient’s life. In chronic, stable conditions, stents are used to significantly improve quality of life, especially in patients with chest pain that persists despite medication. Carotid artery stenoses increase the risk of stroke by jeopardizing blood flow to the brain. In appropriate patients, stenting is an effective and less invasive method to reduce this risk. Stenoses in the leg veins can lead to pain when walking (claudication) and, in advanced cases, gangrene. By opening these vessels, stents restore blood flow, relieve pain and can prevent limb loss.

How has stent technology evolved over the years?

The history of stents is the story of the search for a smarter solution to every problem. This journey has evolved from a simple mechanical solution to smart devices that manage biological processes. It all started in the late 1970s with the idea of dilating blood vessels with just a balloon. this method, called “balloon angioplasty”, was revolutionary but had serious shortcomings. Shortly after the balloon was removed, the dilated vessel could shrink back like a tire and narrow again (elastic retraction). Worse still, in a significant proportion of patients, the vessel would become blocked again within months as the body overreacted with an excessive healing response.

In the mid-1980s, the first Bare-Metal Stents (BMS) were developed as a solution to this mechanical “back-shrinkage” problem. These stents placed a permanent metal scaffold inside the vessel, ensuring that the vessel remained open. This was a big step forward and made stenting a reliable procedure. However, a new problem arose. The body perceived the metal stent as a foreign body and developed a defense mechanism against it. A dense layer of cells (neointima) formed on and inside the stent, similar to wound healing. This is a biological response called “in-stent restenosis”, which causes the inside of the stent to narrow again within months. Approximately -30% of patients with bare metal stents had this problem.

Scientists have found a pharmacological, i.e. medicated, solution to this biological problem. in the early 2000s, Drug-Eluting Stents (DES) came onto the scene. These smart devices contained a special polymer carrier coated on top of a metal skeleton. This polymer slowly released a drug into the vessel wall over a period of weeks that inhibited excessive cell growth inside the stent. The results were spectacular. Drug-eluting stents have revolutionized treatment by reducing the rate of in-stent narrowing to less than 5% and have become today’s gold standard.

But the search was not over. It was thought that a permanent metal implant might cause a chronic reaction in the vessel wall in the very long term (years later) or, in rare cases, lead to clot formation in the late period. This led to the “treat and disappear” philosophy. The result was Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffolds (BVS). These devices are designed to support the vessel for the critical 6-12 months needed for healing, then slowly dissolve over 2-4 years to be completely absorbed by the body. The goal is to leave behind only a healed vessel that has regained its natural function. Although the first generation of dissolvable stents had some technical challenges, studies on this technology shed light on even more biocompatible and effective treatments of the future.

What are the types of stents used today?

A physician’s choice of a stent is similar to a craftsman’s choice of the right tool for the job. Each patient has a different vasculature, stenosis characteristics and general health status. Therefore, a wide variety of stents have been developed to meet these different needs. We can classify stents under several main headings.

Stent application according to its basic technology is as follows:

- Bare Metal Stents (BMS)

- Drug-Eluting Stents (DES)

- Fusible Vessel Scaffolds (BVS)

Drug-eluting stents (DES) are now overwhelmingly the most preferred type of stent for the treatment of coronary artery disease. Their high success rate and very low risk of re-stenosis have made them the standard treatment.

Depending on the placement method, the stent procedure may also differ:

- Balloon Expanding Stents

- Self-Expanding Stents

Almost all stents used in the heart are of the balloon-expandable type. These stents are tightly mounted on a balloon and are advanced into the narrow area, where the balloon is inflated and inserted into the vessel wall. Self-expanding stents are generally preferred in areas that are subject to constant movement and bending, such as the veins in the legs. These stents are made of a special metal alloy (Nitinol) and when the sheath is removed, they automatically return to their pre-programmed shape.

Stents also vary greatly according to the area of use:

- Coronary (Heart) Stents

- Stent-Grafts (for Aorta)

- Peripheral (Leg, Arm) Stents

- Carotid (Carotid Stents)

Each stent is specifically designed for the size of the vessel in which it will be implanted, the speed of blood flow and the mechanical forces to which it will be subjected. For example, a stent-graft used to treat an aneurysm (ballooning) in the aorta, the largest vessel in the body, is a giant structure with a metal skeleton covered with a sealing fabric, while a stent inserted into the tiny vessels of the heart is smaller than a grain of rice.

How is a stent implanted in the heart and how long does stent surgery take?

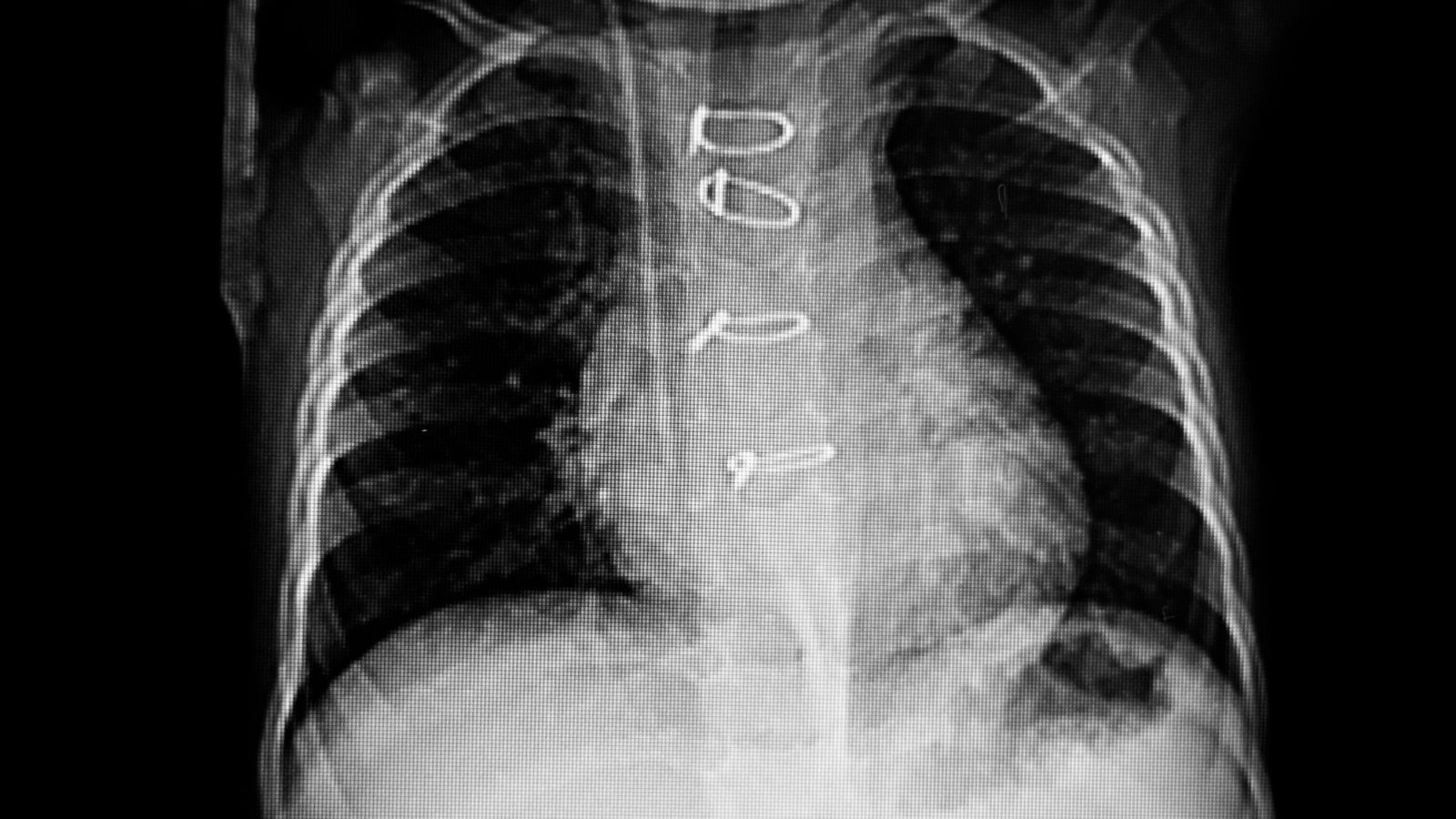

This procedure, which patients often refer to as “stent surgery”, is not actually an open surgical operation. It is called Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) and is performed in a minimally invasive way without making a large incision in the body. The procedure is usually performed in a special room called a “cath lab”, equipped with sophisticated X-ray equipment and monitors, and lasts on average between 30 minutes and 2 hours.

Before a planned procedure, the patient is usually asked to fast after midnight. The physician will explain in detail how to take medications such as blood thinners. Once at the hospital, an IV is started, electrodes are attached to the body to monitor the heart rhythm and a mild sedative is given to relax the patient. The patient is awake and able to talk during the procedure.

The entire procedure is performed through a single small needle puncture. Today, the wrist artery (radial artery) is overwhelmingly preferred for this access. the reason why the “wrist first” approach is preferred is that the risk of complications such as bleeding is much lower and the patient can stand up immediately after the procedure. This increases patient comfort and shortens the hospital stay. The femoral artery in the groin is an alternative for more complex procedures or in rare cases where the wrist vein is not suitable.

After the chosen access site is numbed with local anesthesia, a thin tube called a “sheath” is inserted through this site. Through this tube, a long and flexible tube called a “guide catheter” is advanced under X-ray visualization to the beginning of the vessels supplying the heart. A special dye called “contrast dye” is injected through this catheter. This dye fills the inside of the vessels, creating a road map and clearly showing all the stenoses, blockages and their degree under X-ray.

Once the obstruction has been identified, the treatment begins. A very thin guide wire (about 0.35 mm) is carefully passed through the stenosis. This wire acts like a railroad track. First, a balloon catheter is advanced over the wire and inflated inside the stenosis to pre-expand the vessel. This crushes the plaque and opens the vascular access. The balloon is then removed and a new balloon catheter is advanced over the same wire, on which a compressed stent is mounted. Once the stent is positioned in the center of the stenosis, the balloon is inflated at high pressure. This ensures that the stent is fully expanded and firmly adhered to the vessel wall. Finally, the balloon and wire are removed and the stent is left in place as a permanent scaffold to keep the vessel open.

To make sure the procedure is perfect, especially in complex cases, physicians may resort to intravascular imaging. These techniques, called IVUS (intravenous ultrasound) or OCT (optical coherence tomography), send an ultrasound or light probe into the vessel, allowing us to see the wall structure and the condition of the stent in 360 degrees. This is the most reliable way to confirm whether the stent is expanding, whether it fits snugly against the wall and whether there are any problems with the edges, which significantly increases long-term success.

What should be considered after stent implantation?

Stenting is not the end of treatment but the first step towards a healthy future. The long years of trouble-free operation of the stent depends not only on the success of the procedure, but also on the patient’s lifestyle after the procedure and the care he or she takes in his or her treatment. This process requires a partnership between physician and patient.

The most critical and most important issue is the regular use of medications. The stent is foreign to the body and platelet cells, which are responsible for blood clotting, tend to stick to the metal surface of the stent. This can lead to a sudden blockage of the stent with a clot (stent thrombosis), which is a very dangerous condition that can lead to a heart attack. To eliminate this risk, medications called “dual antiplatelet therapy” (DAPT), commonly known as blood thinners, are prescribed. This treatment usually consists of a combination of aspirin and a second strong blood thinner (such as clopidogrel, ticagrelor or prasugrel). It is vital to take these medicines for as long as your doctor prescribes (usually 6 months to 1 year or longer) without missing a single day.

In addition to medication, permanent lifestyle changes are the most effective way to protect your stent and all your other blood vessels.

Here are the basic lifestyle rules you should follow:

- Definitely quit smoking.

- Adopt a Mediterranean-type diet (vegetables, fruits, whole grains, olive oil).

- Avoid processed foods, excess salt and saturated fat.

- Start a regular exercise program approved by your doctor (usually brisk walking).

- Get rid of excess weight.

- Develop ways to cope with stress.

- Keep your other risk factors such as high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol under control.

- Never miss your scheduled medical check-ups.

How many years will a patient with a stent live and what are the possible risks?

“How long will I live after stent implantation?” is one of the most common questions and concerns of patients. There is no single answer to this question that is clear and valid for everyone. This is because the presence of a stent alone is not a factor that determines life expectancy. A stent is a tool used to treat a disease (vascular occlusion), it does not completely eliminate the disease itself. Life expectancy therefore depends on the person’s general health, how much their heart is affected, whether they have other comorbidities and, most importantly, how well they comply with lifestyle changes and medication after stenting.

What is true is this: A stent, inserted to open a critical stenosis or to save a life during a heart attack, significantly increases the length and quality of life. By opening a nearly blocked artery, it prevents a major heart attack and gives a person a second chance to live a healthy life. A patient who makes good use of this chance, takes his/her medication regularly, eats a healthy diet and plays sports can live as long and high quality life as a healthy individual without a stent.

There are two main risks in the long term after stenting and it is very important to distinguish between them.

In-Stent Stenosis (Restenosis): This is the most common but less dangerous condition. This is when a new layer of tissue gradually forms inside the stent over a period of months or years, narrowing the vessel again. This is not a clotting, but an excessive healing response. Symptoms usually start gradually and are similar to the patient’s complaints before the stent was implanted (e.g. chest pain with exertion). This is not an emergency, but should be recognized and a doctor should be consulted. Thanks to modern drug-eluting stents, the incidence has fallen to less than 5% and can usually be easily treated with drug-coated balloons or a new stent.

Stent Clotting (Thrombosis): This is a much rarer (less than 1%) but extremely serious and urgent condition. This is when a blood clot suddenly forms inside the stent and completely blocks the vessel. This results in a major heart attack and is characterized by symptoms such as sudden, severe chest pain. The most important cause of stent thrombosis is the irregular use of blood thinners or their sudden discontinuation without consulting a doctor. Full compliance with medication is the most effective way to minimize this life-threatening risk.

What does the future of stent technology hold for us?

Innovation in stent technology continues at a dizzying pace. The future goal is not only to mechanically open a blocked vessel, but also to develop biological solutions that fully restore the natural structure and function of the vessel, integrate with the body and even have intelligent properties. the “cure and disappear” philosophy underpins this future.

Here are the exciting developments that await us in the near future:

- Thinner and stronger fusible stents

- Smart stents with sensors

- Bioactive surfaces coated with nanotechnology

- Personalized 3D/4D printed stents

The new generation of dissolvable stents under development are made of metal alloys such as magnesium, which are as strong as metal stents but completely disappear over time. Thanks to miniature sensors that will be implanted, the “smart stents” will be able to continuously measure blood flow, pressure or the risk of clotting and send information wirelessly to the physician. This could help detect problems long before they become symptomatic. Nanotechnology will allow us to design stent surfaces to encourage the growth of vessel-friendly cells and repel clot cells. One of the most exciting developments is 3D-printed customized stents that fit each patient’s individual vascular anatomy. All these technological advances promise to make vascular treatment safer, more effective and more personalized. However, it should not be forgotten that even the most advanced technology cannot replace the patient’s care for their own health and participation in treatment.

Prof. Dr. Yavuz Beşoğul graduated from Erciyes University Faculty of Medicine in 1989 and completed his specialization in Cardiovascular Surgery in 1996. Between 1997 and 2012, he served at Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine as Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor, respectively. Prof. Dr. Beşoğul, one of the pioneers of minimally invasive cardiovascular surgery in Türkiye, has specialized in closed-heart surgeries, underarm heart valve surgery, beating-heart bypass, and peripheral vascular surgery. He worked at Florence Nightingale Kızıltoprak Hospital between 2012–2014, Medicana Çamlıca Hospital between 2014–2017, and İstinye University (Medical Park) Hospital between 2017–2023. With over 100 publications and one book chapter, Prof. Dr. Beşoğul has contributed significantly to the medical literature and is known for his minimally invasive approaches that prioritize patient safety and rapid recovery.