Pericardial effusion is the accumulation of excess fluid in the pericardial sac surrounding the heart. This condition can impair cardiac function by limiting heart movement and may be caused by infections, trauma, malignancies, or systemic diseases such as renal failure.

Symptoms of pericardial effusion include chest pain, shortness of breath, and fatigue, often worsening with lying down. Depending on severity, patients may experience signs of cardiac tamponade, an emergency that requires urgent intervention.

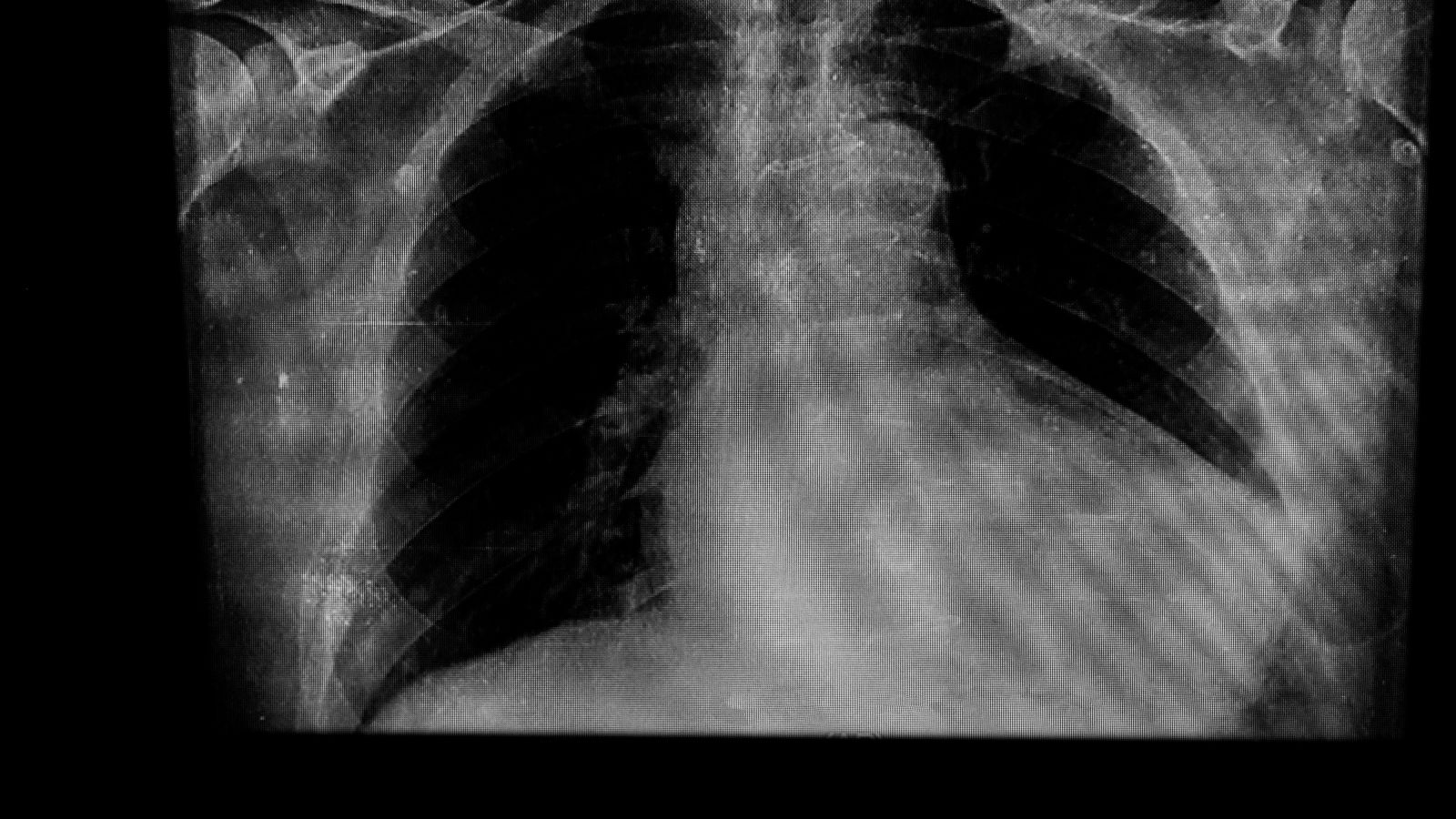

Diagnosis of pericardial effusion is primarily made by echocardiography, which visualizes fluid around the heart. Additional tests such as chest X-ray, CT, or MRI may help in evaluating underlying causes and the extent of fluid accumulation.

Treatment depends on the severity and underlying cause. Mild cases may be monitored with medication, while severe effusions require pericardiocentesis or surgical drainage to relieve pressure and restore cardiac function.

| Medical Name | Pericardial Effusion |

| Common Symptoms | – Chest pain- Shortness of breath- Palpitations- Fatigue- Swelling in the legs or abdomen (in advanced cases) |

| Causes | – Infections (viral, bacterial, tuberculosis)- Cancer- Autoimmune diseases- Renal failure- After heart surgery |

| Risk Factors | – Immune system diseases- History of cancer- Renal failure- Previous heart or pericardial disease |

| Complications | – Cardiac tamponade (compression of the heart)- Heart failure- Blood pressure drop- Shock |

| Diagnostic Methods | – Echocardiography (ECHO)- Chest X-ray- CT or MRI- Blood tests |

| Treatment Methods | – Treatment of the underlying disease- Pericardiocentesis (drainage of fluid with a needle)- Surgical drainage (if necessary)- Drug therapy |

| Prevention Methods | – Control of risk factors – Prevention of infections – Regular medical follow-up |

What Causes Fluid Accumulation Around the Heart?

There is no single cause of fluid accumulation in the pericardium; rather, there is a wide range of diseases and conditions that can lead to this condition. It is very important to understand why this fluid builds up in the first place in order to formulate a proper treatment plan. The main reasons can be grouped under several main headings.

Inflammatory conditions are among the most common causes:

- Viral infections (such as flu, colds)

- Bacterial infections

- Tuberculosis (Tuberculosis)

- Autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis

- Lupus

Sometimes the problem is caused by a disease elsewhere in the body. Systemic diseases that disturb the body’s overall balance can also lead to fluid accumulation. Some of these situations are as follows:

- Cancer (especially lung, breast, lymphoma)

- Chronic renal failure (uremia)

- Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid gland)

- Congestive heart failure

Medical interventions themselves can sometimes cause this problem. Interventions on the heart or trauma to the chest area are also risk factors:

- After open heart surgery

- After interventional procedures such as angioplasty

- Radiotherapy (beam therapy) applied to the chest area

- Hard blows or injuries to the chest

Finally, despite detailed investigations, sometimes the cause of the fluid cannot be found. This condition is called “idiopathic,” meaning “pericardial effusion of unknown cause.”

How Does Accumulated Fluid Affect Heart Work?

The danger posed by fluid accumulating in the pericardium is actually directly related to how fast it accumulates, rather than the amount of fluid. We can think of the pericardium like a balloon. If you inflate it very slowly over a period of days or weeks, the tire will gradually stretch and let in too much air. Similarly, when fluid accumulates slowly, the pericardium stretches and expands over time. This way, the pressure on the heart does not increase too much, even if up to two liters of fluid sometimes accumulate in the pericardium. These patients may experience no symptoms for a long time or only vague complaints, such as a mild shortness of breath that occurs with exertion.

But in cases such as trauma or a rupture of the heart wall, fluid builds up suddenly, within minutes or hours. It’s like suddenly inflating a balloon; the rubber doesn’t have time to stretch and the pressure inside increases rapidly. It is the same with the pericardium. even as little as 150-200 ml of fluid, when it suddenly accumulates, increases the pressure on the heart to dangerous levels. This high pressure squeezes the heart like a vice. The right ventricle and the right atrium, which have thinner walls, are particularly affected by this pressure. The heart cannot relax and fill with blood sufficiently and therefore cannot pump blood to the body. This leads to a life-threatening emergency called “cardiac tamponade”.

Is a water collection in the heart fatal and what is cardiac tamponade?

Yes, the answer to the question “is a collection of water in the heart fatal?” can definitely be “yes” if the condition progresses to cardiac tamponade. Cardiac tamponade is the most dangerous consequence of pericardial effusion. It is the point at which the pressure created by the accumulated fluid exceeds the blood pressure inside the heart. When this happens, the heart is compressed so much from the outside that it can no longer take blood in. Blood returning to the heart from the body cannot get in, so it pools behind, causing the neck veins to swell. Because the heart cannot get blood in, it cannot pump blood to the body. As a result, blood pressure (blood pressure) drops dangerously low, the pulse quickens and the body goes into shock.

Cardiac tamponade does not develop suddenly like an “on-off” switch; it is more of a process. It covers a spectrum ranging from mild hemodynamic disturbance to complete circulatory collapse. It is primarily diagnosed by clinical findings and once diagnosed, it is an absolute emergency where even seconds count. The treatment is to remove the pressure on the heart by draining the accumulated fluid with a needle or surgical method without wasting any time.

What are the Symptoms of Fluid Accumulation in the Heart?

Symptoms of fluid accumulation in the pericardium can vary considerably depending on the amount of fluid, the rate of accumulation and the underlying cause. Sometimes it causes no symptoms at all, and sometimes it can cause serious life-threatening symptoms.

If the fluid accumulation is accompanied by inflammation of the pericardium (pericarditis), typical signs of inflammation are observed. These symptoms include:

- Sharp and stabbing chest pain

- Pain that increases with breathing or coughing

- Pain that decreases when leaning forward and increases when lying on the back

- Fire

- Fatigue

As the amount of fluid increases and starts to put pressure on the heart, symptoms related to impaired circulation come to the fore. The most common of these hemodynamic symptoms are the following:

- Shortness of breath (the most common symptom)

- Increased shortness of breath, especially when lying on your back (orthopnea)

- Palpitations

- Dizziness or feeling faint

- Fatigue and quick fatigue

- Persistent and dry cough

- Abdominal swelling

- Edema in the legs

How is Fluid Accumulation in the Heart Diagnosed?

After listening to the patient’s complaints and performing a physical examination, various diagnostic procedures are used to confirm the diagnosis and determine the severity of the condition. The main purpose of this process is not only to see the fluid but also to measure its amount, to understand how much it affects the heart’s functioning and to get clues to guide treatment.

Echocardiography (ECHO): Echocardiography, also known as ultrasound of the heart, is the gold standard method for diagnosing this disease. Moving images of the heart and surrounding structures are obtained using sound waves. With ECHO, the fluid between the pericardium is clearly visible. The amount of fluid (small, medium, large), its location and which chambers of the heart are under pressure are examined in detail. ECHO plays a vital role especially in detecting early signs of cardiac tamponade. There are some important ECHO findings of tamponade:

- Collapse of the right atrial wall inward

- Collapse of the right ventricular wall during relaxation

- Enlargement of the main vein (vena cava inferior)

- Marked changes in blood flow entering the heart during breathing in and out

Other Imaging Methods: Sometimes, in cases where ECHO is insufficient or more detailed information is required, advanced imaging methods are needed.

Computed Tomography (CT): CT is particularly good at showing whether there is thickening or calcification of the pericardium. These findings suggest that the cause of the fluid may be chronic inflammation and provide the surgeon with an important roadmap for the planned pericarditis treatment or surgery.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR): CMR is the most successful method for tissue characterization. It can clearly show whether there is active inflammation of the lining of the heart or whether the heart muscle itself has developed damage (fibrosis), for example due to radiotherapy. This information is invaluable in predicting the long-term course of the disease (prognosis).

Electrocardiography (ECG) and Blood Tests: The ECG can show typical signs of inflammation of the pericardium (pericarditis). As the amount of fluid increases, the electrical signals from the heart weaken and a condition called “low voltage” appears on the ECG. High levels of inflammatory markers such as CRP in blood tests support an inflammatory process as the underlying cause.

How is the fluid in the heart drained with a needle (pericardiocentesis)?

Pericardiocentesis is a procedure in which fluid accumulated in the pericardium is drained through the skin using a needle and then a catheter (a thin tube). This procedure is both a life-saving treatment in emergencies and an important method that allows us to make a diagnosis by taking a sample from the fluid.

The procedure is usually performed urgently in critically ill patients who have developed cardiac tamponade. It is also performed to relieve a patient when a large amount of fluid is causing severe shortness of breath, even if no tamponade has developed. If we suspect that the cause of the fluid is an infection or cancer, we also use this way to take a sample of the fluid for diagnosis.

However, not all patients are suitable for this procedure. For example, tamponade that develops in cases such as a ruptured aortic vessel or a perforation of the heart wall requires emergency surgery; in these cases, needle intervention can be fatal. Surgical methods are also a safer option in patients with severe blood clotting disorders or when the fluid is very small and hard to reach.

Today, the procedure is almost always performed under echocardiography (ECHO) guidance. This is much safer than doing the procedure blindly. With the patient in a semi-sitting position, the procedure site is numbed with local anesthesia. The ECHO is used to identify the point where the fluid is most abundant and where the needle can be inserted most safely without damaging the heart, lungs or liver. The needle is usually inserted just below the breastbone and the needle is slowly advanced into the pericardial cavity. As soon as fluid comes out, a thin wire is sent through the needle, the needle is withdrawn and a multi-hole, curved-tipped catheter called a “pigtail” is inserted through this wire. This catheter is fixed to the skin and connected to a drainage bag with a closed end, allowing the fluid to drain slowly. Although this procedure has some potential risks, it is quite safe when performed in experienced hands and under imaging guidance. The main complications are:

- Perforation of the heart chambers

- Perforation of the lung membrane (pneumothorax)

- Liver injury

- Serious rhythm disturbances

- Infection

Permanent Solution for Recurrent Fluid: Is Pericardium Surgery (Window Opening) Possible?

After the fluid has been drained by pericardiocentesis, there is a high risk that the fluid will build up again, especially if the underlying cause is cancer or a chronic condition. In such cases, surgical methods are used, which offer a more permanent solution. this surgery for fluid in the heart, called “pericardial window” or “fenestration”, aims to create a hole (window) in the pericardial membrane to allow the fluid to drain continuously into a neighboring cavity (usually the pleura, the lung lining space). This surgery can be performed with two basic techniques:

Subxiphoid Approach (Under the Sternum): This is the traditional method. Through a small incision made at the lower end of the breastbone, the anterior surface of the pericardium is reached and a piece of the membrane is cut out. The main advantage is that it can be performed under local anesthesia and sedatives, without the need for general anesthesia. This makes it a good option for critically ill patients at high risk of general anesthesia. However, the absorption capacity of the upper part of the abdominal cavity where the fluid drains is limited and this window may close over time, causing the fluid to accumulate again. Therefore, the long-term success rate is lower.

VATS (Video Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery – Closed Method): This is a more modern approach that is usually preferred in stable patients. Under general anesthesia, a camera and surgical instruments are advanced through several small holes in the chest wall. The pericardial membrane on the side of the heart is clearly visible under the magnified image from the camera and a large window is cut through the front of the membrane, preserving the phrenic nerve (an important nerve that operates the diaphragm). This window connects the pericardial cavity to the pleural cavity, which has a very large absorption surface. This allows the accumulated fluid to be continuously and efficiently absorbed. VATS has some distinct advantages:

- The recurrence rate of the liquid is much lower

- Provides better visibility and more precise surgery

- If cancer is suspected, targeted biopsies can be taken from suspicious areas

- It is less painful and gives a better cosmetic result

The only disadvantage of this method is that it requires general anesthesia and one lung to be deflated and the respiratory machine to be connected. Therefore, it may not be suitable for hemodynamically unstable, critically ill patients.

In which cases is it necessary to completely remove the pericardium (pericardiectomy)?

Pericardiectomy is one of the most complex operations in cardiovascular surgery and is the latest and most radical option in the treatment of pericardial diseases. The aim of this surgery is not to drain the fluid, but to completely peel and remove the pericardial membrane that has become the disease itself, thickened, hardened and wraps the heart like an armor.

The most important condition in which this major surgery is necessary is chronic constrictive pericarditis. In this disease, after prolonged inflammation (e.g. tuberculosis or recurrent pericarditis) or radiotherapy, the pericardium loses its elasticity, thickens, hardens and even calcifies. This hard sheath prevents the heart from relaxing and filling with blood. Because the heart cannot receive enough blood, blood pools in the body and symptoms of severe heart failure develop. Pericardiectomy is the only effective treatment that removes this mechanical constraint.

The operation is an open heart surgery in which the breastbone is cut all the way through (median sternotomy). This approach allows the surgeon to have access to every part of the heart. The goal of the surgery is called “radical pericardiectomy”. To achieve this goal, there are critical areas where the membrane must be removed:

- The entire anterior surface from one phrenic nerve to the other

- The parts that cover large vessels such as the aorta and pulmonary artery

- The lower, diaphragmatic surface of the heart (the most challenging and most important part)

- Around the main veins (vena cava)

If even a small piece of thickened membrane is left in any of these areas, especially on the undersurface of the heart, the patient’s complaints persist and the operation is considered a failure. Therefore, it is very important that the surgery is performed by experienced surgeons.

What is the Post-Treatment Process and Long Term Results?

Treatment of pericardial effusion does not end when the fluid is drained or the surgery is over. Close follow-up and long-term surveillance after the procedure is as important as the treatment itself to ensure the success of the treatment and protect the patient’s health.

In the immediate post-procedure period, the focus is on detecting possible early complications.

After pericardiocentesis: The patient is kept under observation for at least a few hours under rhythm and blood pressure monitoring. Caution is exercised against conditions such as delayed cardiac perforation or the rare Pericardial Decompression Syndrome.

After surgery: Patients are usually followed up in the intensive care unit for several days. Especially after pericardiectomy, rhythm disturbances such as low cardiac output syndrome and atrial fibrillation may occur frequently and require close follow-up.

Long-term results depend less on the procedure than on the underlying disease that caused the fluid to build up in the first place.

Cancer-Related Fluid Accumulation: Unfortunately, long-term survival in these patients is determined by the type and stage of the underlying cancer. Drainage procedures improve the patient’s quality of life and prevent death from tamponade, but do not change the course of the cancer. Treatment is therefore usually palliative, i.e. comforting.

Unknown (Idiopathic) or Viral Causes: The prognosis in these patients is usually excellent. Once the fluid is under control, the risk of recurrence is low and patients can return to their normal lives.

After Constrictive Pericarditis (Pericardiectomy): Outcomes again depend on the cause. Survival after surgery is very good in idiopathic or post-viral cases. However, the worst results are in cases due to radiotherapy (radiation therapy). This is because radiation permanently damages not only the membrane but also the heart muscle and blood vessels. Even if surgery clears the membrane, the damaged heart muscle remains. Therefore, timing is critical in the treatment of this disease. A pericardiectomy performed before irreversible damage to the heart muscle occurs offers the best results.

Prof. Dr. Yavuz Beşoğul graduated from Erciyes University Faculty of Medicine in 1989 and completed his specialization in Cardiovascular Surgery in 1996. Between 1997 and 2012, he served at Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine as Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor, respectively. Prof. Dr. Beşoğul, one of the pioneers of minimally invasive cardiovascular surgery in Türkiye, has specialized in closed-heart surgeries, underarm heart valve surgery, beating-heart bypass, and peripheral vascular surgery. He worked at Florence Nightingale Kızıltoprak Hospital between 2012–2014, Medicana Çamlıca Hospital between 2014–2017, and İstinye University (Medical Park) Hospital between 2017–2023. With over 100 publications and one book chapter, Prof. Dr. Beşoğul has contributed significantly to the medical literature and is known for his minimally invasive approaches that prioritize patient safety and rapid recovery.