Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a small hole between the atria of the heart that persists after birth. While often asymptomatic, it can allow abnormal blood flow and, in rare cases, contribute to conditions like stroke or migraine.

Clinical significance arises when paradoxical embolism occurs, where a blood clot bypasses the lungs and reaches systemic circulation, potentially causing neurological events such as transient ischemic attack or stroke.

Diagnosis is typically made with echocardiography, particularly transesophageal echocardiography with bubble study, which demonstrates abnormal passage of blood or microbubbles between the atria.

Treatment is individualized, ranging from observation in asymptomatic patients to percutaneous closure in patients with recurrent embolic events. Antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy may also be recommended depending on risk.

| Medical Name | Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO) |

| Common Symptoms | – Usually asymptomatic – Rarely stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) – Migraine of unexplained cause |

| Causes | – Congenital (failure of the heart-to-heart passage, which is normal in the fetal period, to close after birth) |

| Risk Factors | – Family history of PFO- Congenital heart disease |

| Complications | – Clot in the brain (cryptogenic stroke)- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)- Rarely, clot formation in the heart |

| Diagnostic Methods | – Echocardiography (especially contrast-enhanced ECHO or transesophageal ECHO)- Bubble test |

| Treatment Methods | – Generally no treatment required- Anticoagulant drugs if previous stroke or TIA- Intervention with percutaneous closure device if necessary |

| Prevention Methods | – Regular follow-up in high-risk individuals – Healthy lifestyle and medical measures to reduce coagulation risk |

What is Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO)?

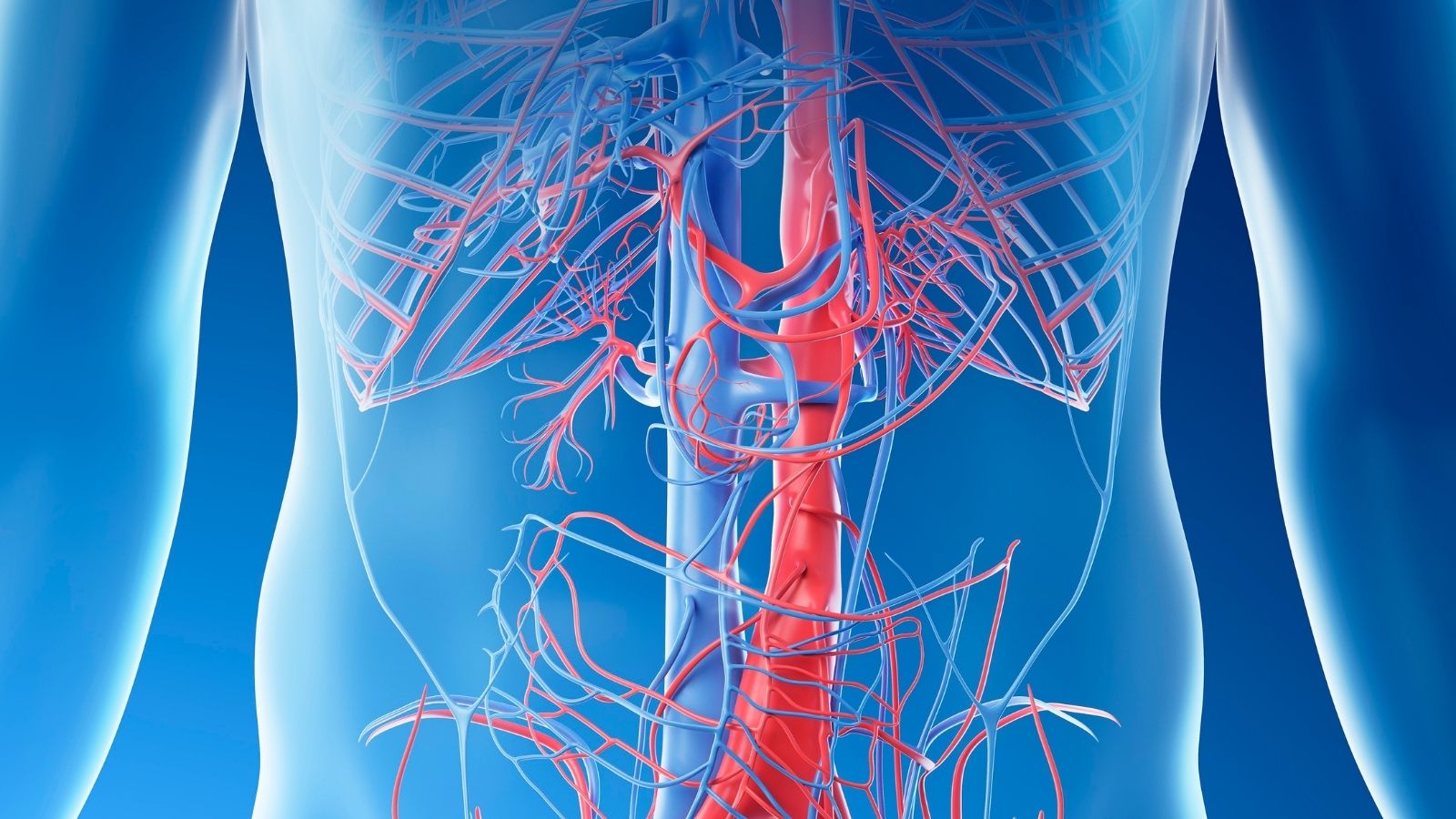

To understand PFO, we need to take a short journey into life in the womb. Since a baby in the womb does not breathe, it does not get oxygen from the lungs but directly from the mother’s placenta. Oxygen-rich blood from the placenta reaches the right atrium of the baby’s heart. This is where the small door called the foramen ovale comes into play. This door allows oxygenated blood to pass from the right atrium of the heart directly to the left atrium, instead of going to the lungs, which are not yet working. From there, blood is pumped to the brain and other vital organs. This is an excellent and vital circulatory pathway for the baby’s development in the womb.

When the moment of birth arrives and the baby takes its first breath, everything changes. The lungs fill with air and begin to clear the blood. This increases the amount of blood returning to the left side of the heart, increasing the pressure in the left atrium. This increased pressure pushes the foramen ovale valve closed. In most babies, these valves completely fuse together and close permanently within the first few months after birth. However, in about % of the population, this complete fusion does not occur and remains as a potential gateway. This is what we call Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO).

It is very important to understand that a PFO is not a true “hole in the heart” like an atrial septal defect (ASD), which is a structural defect. Let us examine the following items to get a clearer picture of the main differences between them.

The main differences between PFO and ASD (Atrial Septal Defect) are as follows:

- A PFO is a functional valve left over from normal fetal anatomy.

- An ASD is a true structural hole in the heart wall caused by a lack of tissue.

- In a PFO, blood passage usually only occurs when right heart pressure increases (e.g. when pushing, coughing).

- In ASD, blood flow is usually continuous and from left to right.

- PFO is very common (~% of the population).

- ASD is a much rarer condition.

Therefore, a person with a PFO usually does not have symptoms of patent foramen ovale. This is often an incidental finding during an ultrasound of the heart performed for another reason.

When is PFO Dangerous and What Risks Does it Carry?

While the vast majority of individuals with PFO live their entire lives unaware and healthy, the question of when is PFO dangerous becomes important in certain scenarios. PFO becomes a potential risk through a mechanism called “paradoxical embolism”. Let’s try to understand this mechanism step by step.

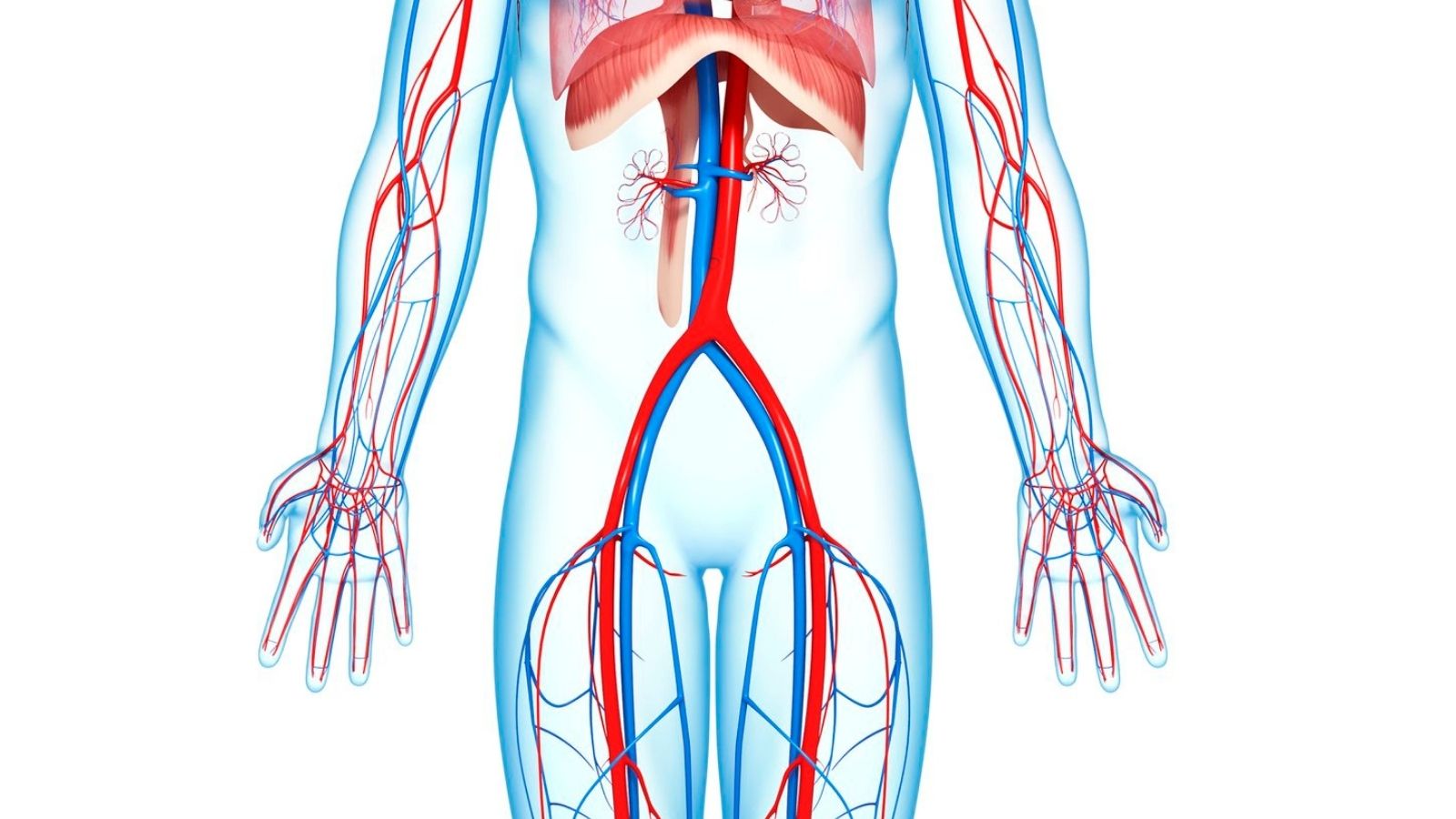

Small blood clots can sometimes form in the veins of the body, especially in the deep veins of the legs. In normal, healthy circulation, these clots are carried by the blood flow to the right side of the heart, where they are pumped to the lungs. Our lungs are like a huge and delicate filter made up of millions of capillaries that catch these tiny clots and safely remove them from the bloodstream. This is the body’s self-protection mechanism.

But in a person with PFO, things can change a little. For example, when lifting heavy objects, having a severe coughing attack or straining, the pressure inside the chest suddenly increases. This increase in pressure also increases the pressure on the right side of the heart, momentarily opening the normally closed PFO valve. At that very moment, a small clot coming from the legs, instead of going to the lung filter, finds a “shortcut” through this open door, the PFO, and goes directly to the left side of the heart.

This clot, which passes to the left side of the heart, now enters the arterial system that pumps clean blood throughout the body. If this clot blocks one of the delicate arteries to the brain, blood flow to that area of the brain is cut off, resulting in an ischemic stroke (paralysis). This is called a “paradoxical” embolism because a problem that starts in the venous system unexpectedly leads to a serious problem in the arterial system through the PFO.

Not all PFOs carry the same risk. Some anatomical features may make a PFO more dangerous by increasing the risk of paradoxical embolism. We always consider these high-risk features when making treatment decisions.

Anatomical factors that make PFO more risky:

Atrial Septal Aneurysm (ASA): A condition in which the wall between the atria of the heart is more flexible, mobile and fluctuates like a sail. This excessive mobility causes the PFO tunnel to open more easily and frequently. The presence of ASA with PFO significantly increases the risk of stroke compared to PFO alone.

Large Right-to-Left Shunt: A large number of microbubbles pass from the PFO to the left side of the heart during a bubble test. This indicates a large amount of blood leakage through the PFO. Logically, a larger leak can allow the passage of larger clots.

Long PFO Tunnel: A tunnel length of more than 10 mm in the PFO duct may also be considered a risk factor for clots to stall and become lodged in this tunnel.

Prominent Eustachian Valve: An anatomical structure located in the right atrium that can direct blood flow directly into the PFO tunnel. This may facilitate the diversion of clots to the PFO.

What Is the Connection Between Cryptogenic Stroke and PFO Treatment?

In approximately 0-40% of all ischemic strokes, no clear cause of the stroke can be found despite all detailed examinations. All possible causes such as heart rhythm disorders, carotid artery stenosis, clotting disorders are investigated but no conclusion is reached. In medicine, this condition is called “cryptogenic stroke” or “stroke of unknown cause”.

This is where the link between PFO and cryptogenic stroke becomes critically important. Epidemiologic studies have clearly demonstrated that the incidence of PFO in patients with cryptogenic stroke, especially those under 60 years of age, is almost twice as high (@-50%) compared to the general population (%). This striking statistical association is the strongest evidence that PFO may be the main mechanism underlying such strokes.

One of the most important challenges in clinical practice is to distinguish whether the PFO detected in a patient with cryptogenic stroke is the real “perpetrator” of the event or just an “innocent bystander”. Evidence-based tools such as the “RoPE (Risk of Paradoxical Embolism)” score are used to make this distinction. The logic of this score is quite simple: The younger a patient is and the fewer traditional stroke risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and smoking, the more likely it is that their stroke was caused by a rarer cause such as a PFO.

Factors that increase the RoPE score and thus the likelihood of stroke originating from a PFO are:

- Young age (18-29 years old score the highest in the score)

- No history of hypertension

- No history of diabetes

- Not being a smoker

- No previous stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Brain imaging shows a superficial (cortical) infarct

A high RoPE score (usually 7 and above) suggests that the stroke is highly likely to be associated with a PFO, reinforcing the decision that closure as PFO treatment may be beneficial. Therefore, when cryptogenic stroke is diagnosed in a young patient, investigating for the presence of PFO and its risk factors has now become an integral part of the standard diagnostic evaluation.

Which Methods are Used for PFO Diagnosis?

When a patient is suspected to have a PFO, the diagnostic process is usually carried out with imaging tests based on showing the right-to-left blood flow (shunt) through the PFO. There are basic diagnostic tools and steps used in this process:

The diagnostic pathway for PFO is usually as follows:

Screening with Transthoracic Echocardiography (TTE): It is usually the first method used. It is a standardized ultrasound of the heart that is performed through the chest wall, is painless and does not require any intervention to the body. Although it is an ideal screening tool, the image quality may decrease and some PFOs may be missed, especially in obesity or certain lung diseases. Therefore, a normal TTE result does not definitively exclude the presence of PFO.

Bubble Study: The keystone of PFO diagnosis. This test is performed during TTE or the next step, TEE. Millions of harmless microbubbles created by agitating sterile serum and a small amount of air are injected through a vein in the patient’s arm. In a normal heart, these bubbles travel from the right side of the heart to the lungs and are filtered there; they are never seen on the left side of the heart.

Valsalva Maneuver To increase the sensitivity of the test, the patient is asked to hold their breath and push during the bubble injection. This maneuver increases intrathoracic pressure, facilitating the opening of the PFO valve and bubble passage. If a PFO is present, during this maneuver it is clearly seen that some of the bubbles leak through the PFO channel and appear on the left side of the heart.

Confirmation by Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE): It is considered the most reliable and definitive method, the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of PFO. In this method, a flexible tube with a small ultrasound camera at the end is inserted through the esophagus just behind the heart. In this way, much clearer, high-resolution images are obtained without intervening tissues. TEE allows direct visualization of the presence of the PFO tunnel, its size, length, high-risk anatomical features such as associated atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) and, most importantly, the passage of bubbles through the PFO. It is an indispensable method in treatment planning as it provides all the anatomical details necessary for a potential closure procedure.

PFO Treatment: Should Medication or Closure Procedure be Required?

In a patient who has had a cryptogenic stroke associated with PFO, there are two main treatment strategies to prevent a similar event in the future: medical (drug) treatment and percutaneous (non-surgical) patent foramen ovale closure.

Medical treatment includes medicines that make blood clotting more difficult. This approach aims to provide indirect protection by reducing the risk of clots forming. Closure, on the other hand, focuses on the source of the problem – the shortcut taken by the clots – and permanently closes this anatomical gateway.

In the past, there was no scientific consensus on which of these two methods was superior. However, large randomized controlled trials such as RESPECT, REDUCE and CLOSE, published after 2017 and groundbreaking in the medical world, put an end to this debate. These studies conclusively and unequivocally showed that in carefully selected groups of patients (usually aged 18-60 years, with stroke without other causes and with high-risk PFO characteristics), PFO closure reduces the risk of recurrent stroke much more than drug therapy alone. In light of this evidence, current international cardiology and neurology guidelines recommend PFO closure as the most effective treatment for the right patient.

Comparison of two treatment approaches:

Drug Therapy (Antiplatelet/Anticoagulant):

Objective: Preventing the formation of new clots or the growth of existing clots.

Method: Drugs that prevent blood platelets from sticking, such as aspirin or clopidogrel, are usually used.

Disadvantage: Does not close the PFO duct, only reduces the risk of clots. There are risks of lifelong medication and potential bleeding. It does not reduce the risk of stroke from PFO as effectively as closure.

Percutaneous PFO Closure Procedure:

Objective: Physically and permanently closing the PFO tunnel, the passageway for clots.

Method: A closure device is placed in the PFO through a minimally invasive catheter procedure.

Advantage: Eliminates the source of the problem. It reduces the risk of recurrent stroke in evidence-based selected patients in a way that is far superior to drug therapy.

Therefore, the most effective prophylaxis strategy for a suitable patient with cryptogenic stroke and PFO is nonoperative closure of the PFO.

How is Non-Surgical PFO Closure Procedure Performed?

Percutaneous PFO closure is a comfortable and modern minimally invasive procedure performed without the need for open heart surgery. The procedure is usually performed in a catheterization laboratory, with the patient in a light sleep state (conscious sedation) and only the access site numbed with local anesthesia. The whole process usually takes less than 1 hour and is quite comfortable for the patient.

The step-by-step process is as follows:

Preparation and Anesthesia: The procedure is usually performed in the right groin area. This area is cleaned with antiseptic solutions and the point where the catheter will enter is numbed with a local anesthetic needle. This way, the patient does not feel any pain during the procedure.

Vein Access: A needle is inserted into the large vein (femoral vein) in the anesthetized groin area and a short, plastic tube called a “sheath” is inserted into the vein at this entry point. All catheters and devices will enter and exit the body through this sheath.

Access to the heart Through this sheath, a long, thin and flexible tube called a “catheter” is advanced. This catheter travels through the blood vessels to the right atrium (right atrium) of the heart. Every moment of this journey is continuously monitored under the guidance of fluoroscopy (a mobile X-ray device) and echocardiography (usually TEE).

Passage through the PFO: Once the right atrium is reached, an even thinner guidewire is advanced through the catheter and carefully passed through the PFO tunnel to reach the left atrium (left atrium) of the heart. It is like building a bridge to move this device to the right place:

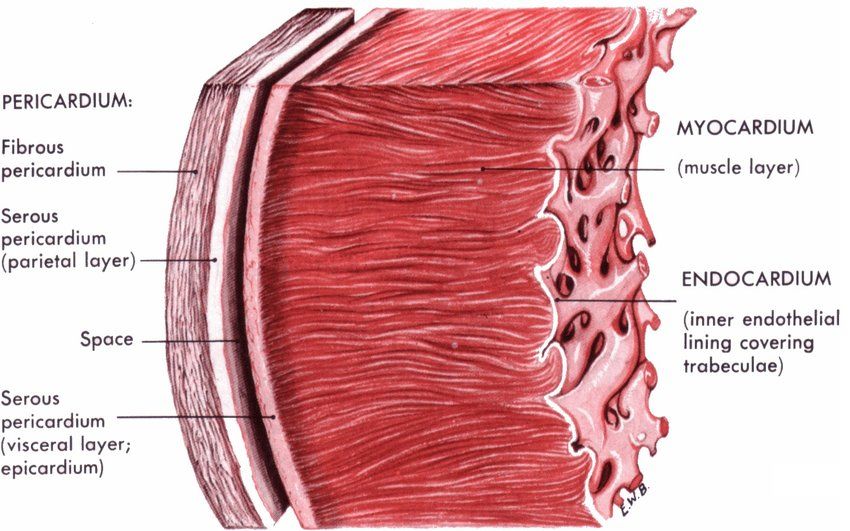

Device Placement: The correctly sized closure device is loaded into a delivery catheter system and advanced over the guidewire to the PFO. The device consists of two umbrella-like disks connected by a narrow waistband. First, the disk of the device that will remain in the left atrium is removed from the catheter and opened. This disk is gently leaned back against the heart wall (interatrial septum). Then, the catheter is pulled back a little further and the disk of the device in the right atrium is also opened. With this maneuver, the PFO is completely closed by sandwiching it between these two disc umbrellas.

Final Check and Completion of the Procedure: It is carefully checked by echocardiography that both discs of the device are seated against the heart wall, are in the correct position and do not compress adjacent vital structures such as the aorta or heart valves. Once everything is confirmed to be perfect, the device is released from the delivery system (usually by a screw mechanism) and left permanently in the heart. The delivery system, catheter and sheath are removed from the body. The vein entry point in the groin is usually closed using a special suture or closure device and a small bandage is applied.

The devices used in this process are made of a “shape memory” metal alloy of nickel and titanium called “Nitinol”. The great feature of this material is that even when compressed into a thin catheter, it can return to its original, programmed umbrella shape when released. This allows for minimally invasive implantation of the device. The metal skeleton of the device is covered with a biocompatible fabric that encourages the body’s own cells to grow over the device over time and completely cover it. Within a few months, the device becomes part of the body and is completely isolated from the bloodstream.

What Should Be Considered After PFO Closure?

The recovery process after percutaneous PFO closure, which is a minimally invasive procedure, is much faster and more comfortable compared to open heart surgery. Things to be considered after PFO closure can be categorized under several headings.

Things to consider in the first days after the procedure:

- The patient is followed in an observation room for several hours after the procedure.

- To minimize the risk of bleeding at the entry site in the groin, the patient may need to lie on their back without bending their leg for several hours.

- If no problems develop, patients are usually discharged in the evening of the same day as the procedure or the following morning.

- Most patients can return to their normal daily activities and work life in as little as one week.

Medication and activity restrictions:

Medication Therapy: This is the most important step after the procedure. Until the device is completely covered with the body’s own tissue (this process usually takes 3-6 months), patients are prescribed blood thinners to prevent clot formation on the metal surface of the device. Dual antiplatelet therapy (a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel) is usually used for the first 1-6 months. After this period, it is generally recommended to continue single antiplatelet therapy (aspirin only) for life.

Activity Restrictions: Patients can walk immediately, but it is important to avoid lifting objects heavier than 5 kg, forceful straining movements and strenuous exercise for the first week. They can usually start driving after a few days.

Endocarditis Prophylaxis: During the first 6 months following implantation of the device, precautions may need to be taken against the very rare risk of an infection elsewhere in the body entering the bloodstream and settling in the device (infective endocarditis). Therefore, it may be recommended to use antibiotics for preventive purposes before tooth extraction or other surgical procedures to be performed during this period.

Long-term follow-up plan:

- Patients need regular follow-up to assess the success of treatment and possible complications.

- The standard follow-up schedule usually includes checks with ECG and echocardiography at 1 month, 6 months and 1 year after the procedure:

- 6. the moon check is particularly important to confirm that the appliance is completely covered and that there are no leaks or clots.

Are There Risks and Side Effects of PFO Closure?

Percutaneous PFO closure is a procedure that has been performed in tens of thousands of patients and has a proven high safety profile. With modern devices and in experienced hands, the rate of serious complications associated with the procedure is usually less than 1%. However, as with any medical procedure, there are some potential risks and complications. Being transparent about these risks is essential for patient trust.

Potential risks of PFO closure:

Entry Site Complications: Problems such as minor bleeding, bruising (hematoma) or pseudoaneurysm formation in the groin area where the catheter enters. These are often the most common problems, but the simplest and most manageable.

Device Embolization: This is when the closure device detaches from its implantation site and travels through the bloodstream to another chamber of the heart or into the pulmonary vessels. This is extremely rare (<1%) and requires urgent intervention and removal of the device, either by catheterization or surgically.

Device Thrombosis: The formation of a blood clot on the surface of the device, especially if post-procedure medication is not used regularly. This emphasizes the importance of post-procedure medication.

Cardiac Perforation: This is when the catheter or device perforates the heart wall during the procedure and blood accumulates between the pericardium and the heart muscle. This is a life-threatening but very, very rare complication that requires urgent intervention.

Atrial Fibrillation (AF): The most common side effect after the procedure is atrial fibrillation, a type of arrhythmia. It occurs in approximately 5-7% of patients undergoing the procedure, usually immediately after the procedure or within the first few weeks. This is thought to be due to local mechanical stimulation and edema of the heart wall caused by the device itself. This arrhythmia is largely transient and disappears once the device is covered with tissue and healing is complete. It is usually easily managed with medication. It is generally considered a temporary and manageable risk, with a significant reduction in the risk of stroke, a devastating event.

Prof. Dr. Yavuz Beşoğul graduated from Erciyes University Faculty of Medicine in 1989 and completed his specialization in Cardiovascular Surgery in 1996. Between 1997 and 2012, he served at Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine as Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor, respectively. Prof. Dr. Beşoğul, one of the pioneers of minimally invasive cardiovascular surgery in Türkiye, has specialized in closed-heart surgeries, underarm heart valve surgery, beating-heart bypass, and peripheral vascular surgery. He worked at Florence Nightingale Kızıltoprak Hospital between 2012–2014, Medicana Çamlıca Hospital between 2014–2017, and İstinye University (Medical Park) Hospital between 2017–2023. With over 100 publications and one book chapter, Prof. Dr. Beşoğul has contributed significantly to the medical literature and is known for his minimally invasive approaches that prioritize patient safety and rapid recovery.