Heart valve prostheses are classified into mechanical and biological valves, each with specific advantages and limitations. They are implanted in patients with severe valvular disease who require valve replacement.

Mechanical heart valves are highly durable and can last a lifetime, but they require lifelong anticoagulation therapy to prevent clot formation. They are generally recommended for younger patients.

Biological valves, derived from animal or human tissue, do not usually require long-term anticoagulation. However, they are less durable and may require reoperation after 10–20 years, making them more suitable for older patients.

The choice between mechanical and biological valves depends on age, lifestyle, comorbidities, and patient preference. Proper patient counseling ensures optimal selection and improved long-term outcomes.

What are the main differences between mechanical and biological heart valves and what materials are they made of?

The first step in the treatment journey is to understand the options. Understanding the distinction between Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves is fundamental to this process. In its simplest form, this distinction is based on a balance between endurance and the need for blood thinners.

Mechanical Heart Valves (MCH)

You can think of mechanical valves as a marvel of engineering. They are made of highly durable synthetic materials that are compatible with the human body. The most common modern designs today consist of two small leaflets that open and close in perfect timing, allowing blood to flow only forward. The main material from which these valves are made is pyrolytic carbon. This is a special carbon with a hardness close to diamond, with a mirror-smooth surface that prevents blood from sticking to it. Thanks to these features, they are also popularly known as “metal heart valves”.

The most striking feature of mechanical valves is their extraordinary durability. Patients often ask “how long does a mechanical heart valve last?” and the answer is very pleasing: theoretically a lifetime. These valves do not degrade structurally, making them an excellent option, especially for young patients with a long life expectancy.

But with this longevity comes an important responsibility. The artificial surface of the valve can activate the natural clotting mechanism of the blood. Therefore, patients need to take a blood thinner (warfarin) for life to prevent clots forming on the valve and traveling to vital organs such as the brain and causing paralysis. This is the most important condition for mechanical valve selection.

Biological (Bioprosthetic) Heart Valves (BKK)

Biological valves, as the name suggests, are derived from living tissue. The main sources used in the production of these valves are:

- Porcine (porcine) heart valves

- The membrane (pericardium) tissue surrounding the bovine heart

These animal tissues undergo special chemical treatments to make them more durable and to prevent the human body from recognizing and rejecting them as foreign. It is then carefully stitched by hand onto a frame (stent) to give it its final shape.

The biggest advantage of bioprostheses is that they work in perfect harmony with the blood and have a very low risk of clot formation. This means that the vast majority of patients with this valve do not need to take blood thinners for life. This makes them an ideal option for patients at risk of bleeding, who may find it difficult to have regular blood tests, or who want to avoid the lifestyle changes that blood thinners bring.

In exchange for this advantage, they have a more limited durability. Over time, this biological tissue can develop structural valve degeneration (SVD), a process we might call “wear” or “aging”. This means that the tissue hardens, calcifies or ruptures. In such a case, a second operation may be required to replace the deteriorated valve. Generally, the lifespan of a biological valve ranges from 10 to 20 years, but this varies depending on the age of the patient. The valves tend to last longer in older patients because the body’s calcium metabolism is slower.

What are the main complications and risks associated with Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves?

Although both types of valves are life-saving, they carry their own potential risks. Knowing these risks associated with Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves is a prerequisite for making an informed decision.

Risks Specific to Mechanical Valves

Concerns about mechanical valves stem mainly from the need to use blood thinners. This entails some risks.

The most important risks are:

- Thromboembolism: When the dose of blood thinners is insufficient, a clot forms on the valve and travels through the bloodstream to organs such as the brain.

- Valve Thrombosis: The clot that forms and prevents the valve from moving, leading to heart failure.

- Bleeding: Unexpected or trauma-induced serious bleeding in any part of the body (stomach, brain, urinary tract, etc.) due to the use of blood thinners.

- Pannus Formation: Over time, a layer of abnormal tissue grows around the valve’s suture ring, restricting its movement.

Risks Specific to Biological Valves

The risk profile of biological valves is due to their biological nature, i.e. they wear out over time.

The most common problems are the following:

- Structural Valve Degeneration (SVD): This is the most fundamental problem of biological valves. Over time, the valve tissue calcifies, hardens or ruptures, resulting in impaired valve function.

- Reintervention (Reoperation): When SVD progresses, a second surgery or intervention is required to replace the deteriorated valve.

- Valve Thrombosis: Although much rarer than mechanical valves, clots can also form in these valves, especially in the first months after surgery.

Risks with Both Valve Types

Some risks are independent of the type of valve.

These are shared risks:

- Infective Endocarditis: This is when germs that enter the bloodstream from a focus of infection elsewhere in the body (such as a dental abscess) settle on the prosthetic valve and multiply there. This is a rare but serious and life-threatening condition that is difficult to treat.

- Paravalvular Leak (PVL): The leakage of blood is not from the valve itself but from the edge of the suture ring where the valve is sewn to the heart.

What factors do current medical guidelines consider when choosing between Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves?

In the past, valve selection was a process that depended more on the decision of the surgeon, but today this understanding has completely changed. In modern medicine, the principle of “shared decision making” is essential when choosing between mechanical and biological heart valves. This means that your values, lifestyle and expectations come together with your physician’s medical knowledge to make the best decision.

The key factors we put on the table in this joint decision-making process are the following:

- Your age

- Your general health and life expectancy

- Whether you can take blood thinners regularly

- Whether you have another disease that increases your risk of bleeding

- Your profession and lifestyle (for example, if you are an active athlete)

- How you approach the idea of having another surgery in the future

- For female patients, whether you have a pregnancy plan

If we draw a general framework, in patients under the age of 50-55 years, the lifelong durability of mechanical valves comes to the fore due to long life expectancy. in patients over 65-70 years of age, it becomes more important to avoid the risk of bleeding associated with the use of blood thinners, and the 15-20 year lifespan of biological valves is considered sufficient.

The group that is most important and where the decision is most individualized is patients between 50 and 69 years of age. In this “gray zone” both types of valves can be a reasonable option and all the other factors listed above become much more important. For example, a mechanical valve may make more sense for a 60-year-old patient who already has to use blood thinners for another reason (such as atrial fibrillation), whereas a biological valve may be a better choice for another patient of the same age who is actively mountaineering and fears the risk of bleeding.

What do long-term results with Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves mean, especially for middle-aged patients?

Traditionally, valve selection for patients aged 50-69 years was often seen as a lifestyle choice. However, over the last decade, large-scale studies have changed this perspective by demonstrating that this decision can potentially affect long-term survival. The most striking data comes from the Swedish Cardiac Surgery Registry, which covers the whole country.

These studies have shown that in patients aged 50-69 years undergoing aortic valve replacement, mechanical valves provide a significant survival advantage over biological valves when mechanical and biological heart valves are compared. This advantage becomes even more pronounced as the age range narrows, especially in the 50-59 age group.

This is thought to be due not only to the fact that biological valves require reoperation. A more likely explanation is that the process of biological valve deterioration (SVD) is quite insidious. The valve can cause the heart to exert more effort and work inefficiently for months or even years, long before the patient’s symptoms become severe enough to warrant reoperation. This prolonged latent load can lead to permanent fatigue and damage to the heart muscle over time, with a negative impact on long-term survival independent of the reoperation itself. Therefore, especially in discussions with these middle-aged patients, it is clear that the decision is not only a choice between bleeding risk and lifestyle freedom, but also requires a more comprehensive assessment that includes this potential survival advantage offered by the mechanical valve.

How does quality of life differ with mechanical and biological heart valves, especially in terms of the use of blood thinners?

There has long been a prevailing assumption in the medical community and among patients: The lifelong blood thinner treatment required by mechanical valves significantly reduces the patient’s quality of life compared to biological valves. This has been one of the main arguments behind the popularity of biological valves. However, recent scientific studies show that this assumption is not quite correct.

Surprisingly, many studies using standardized quality of life questionnaires have found no significant difference between the overall quality of life of patients living with Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves, despite all the challenges of blood thinner use. And how is this possible?

This can be explained by a psychological phenomenon we might call the “balance of burdens”. On the one hand, mechanical valve patients have a tangible daily “management burden”: regular blood tests, dietary restrictions, constant vigilance for the risk of bleeding and sometimes even the audible sound of the mechanical heart valve. On the other hand, patients with biological valves are exempt from these daily burdens, but they too carry a different burden: the lingering background uncertainty and “anxiety about future reoperation” caused by the awareness that their valves have an “expiry date”. It seems that the constant and tangible stress experienced by one is somehow offset by the stress of uncertainty about the future experienced by the other, resulting in similar levels of overall life satisfaction for both groups. This finding highlights once again how personal the decision is. The question becomes, “Which burden do you prefer to carry?”

How do modern valve procedures influence the choice of Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves?

Deciding on the type of valve is only one side of the equation. The other side is how this valve will be implanted in the heart. Today, there are two main methods and which method you choose can directly affect your choice between Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves.

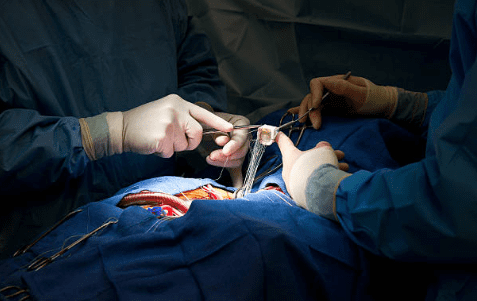

- Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR)

This is the traditional open-heart surgery that has been the “gold standard” treatment for aortic valve disease for decades. In this procedure, the sternum is cut to expose the heart, the heart is stopped, the patient is connected to a heart-lung machine and the surgeon completely removes the diseased valve and sutures a new prosthetic valve in its place. One of the most important advantages of the SAVR procedure is that it offers the surgeon the flexibility to place both mechanical and biologic valves.

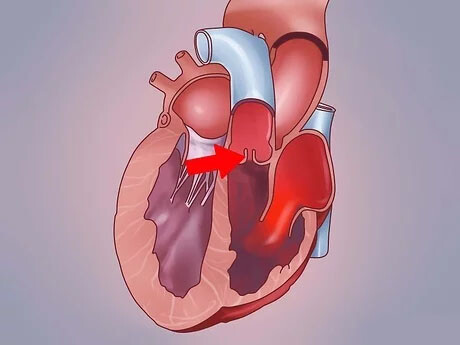

- Catheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI or TAVR)

This is a revolutionary, minimally invasive procedure developed in the last 20 years. It does not require open heart surgery. A small incision is usually made in the groin artery and a catheter is used to deliver the new valve, which is compressed at the end of a catheter, to the heart. The new valve is inserted into the patient’s own calcareous valve and expanded, pushing the old valve to the edges and into place. The key technological feature of TAVI is that the valve is compressible enough to fit inside a catheter. This technology is currently only available for biological valves made from animal tissue. Mechanical valves cannot be compressed in this way because of their hard and rigid structure. So when a patient and their heart team choose the TAVI procedure, the valve type discussion automatically ends; the option is only a biological valve.

Which patients are suitable for TAVI and how does this choice limit the decision between Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves?

The success of TAVI relies heavily on the right patient selection. Not every aortic stenosis patient is suitable for TAVI. A “Heart Team” consisting of a cardiac surgeon, interventional cardiologist, cardiac anesthesiologist and cardiac imaging specialists makes this important decision.

The clinical criteria that determine eligibility for TAVI are:

- Symptoms of severe aortic stenosis (shortness of breath, chest pain, fainting, etc.)

- The patient is at high risk for open heart surgery

- Advanced age of the patient (usually over 75-80 years)

- The patient’s general state of health is poor and “fragile”

- Presence of additional diseases such as serious lung and kidney diseases that increase the risk of open surgery

The patient’s anatomy must also be suitable for this procedure. This suitability is determined by detailed measurements using computed tomography. If the Heart Team decides that TAVI is the most suitable procedure for a patient, then there is no choice between Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves. Due to the nature of the procedure, the patient will necessarily be fitted with a biological valve.

Between Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves, what does long-term care for a patient with a mechanical valve include?

Living with a mechanical valve requires bringing a new order to your life. This means becoming an “active manager” of your own health. This new order is a responsibility you must take on in exchange for the assurance of a valve that will last a lifetime.

The most important element of this management plan is the careful management of blood thinner (warfarin) treatment. The effectiveness of the medicine is checked regularly with a simple blood test called the INR. Your doctor will set a target INR range for you. Going outside this range increases the risk of clots or bleeding. You should pay particular attention to some points when using this medicine.

For example, you should not suddenly and excessively change the amount of vitamin K-rich foods in your diet. It is important not to cut these foods out completely, but to keep their consumption in balance. Some of these foods are as follows:

- Spinach

- Chard

- Kale

- Broccoli

- Brussels sprouts

- Parsley

- Purslane

It is also important to avoid contact sports or activities with a high risk of falls, which may increase the risk of bleeding. Another important issue is the risk of prosthetic valve infection. To prevent this, you should take good care of your oral and dental health and use preventive antibiotics before bleeding procedures such as tooth extraction.

The mechanical heart valve sound, which many patients are curious about, is a rhythmic sound similar to the tick-tock of a clock, usually heard in a quiet environment. This sound is an indication that your valve is functioning properly and most patients get used to it over time.

Between Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves, what should be the long-term follow-up and lifestyle for a patient with a biological valve?

Living with a biological valve can feel more “free” as there are fewer restrictions in daily life. However, this does not mean that follow-up is less important. The “active partnership” here means that the patient listens carefully to his or her own body and keeps regular check-ups, being aware that the valve may wear out over time.

When comparing Mechanical and Biological Heart Valves, the main objective in the follow-up of biological valves is to detect structural valve degeneration (SVD) at an early stage. For this reason, it is very important to be checked with echocardiography (ultrasound of the heart) at intervals determined by your doctor (usually annually, starting a few years after surgery).

You should also be alert to the signals your body is sending you. If the symptoms you experienced before surgery gradually return, this may indicate a problem with your valve. These are the symptoms you should look out for:

- Shortness of breath, especially with exertion or when lying down at night

- Getting tired much more quickly than usual

- Chest pain or feeling of pressure

- Dizziness or fainting

- Swelling in the ankles or legs

If you notice any of these symptoms, you should contact your doctor immediately, without waiting for your next appointment. Remember, when SVD progresses, a second open-heart surgery is no longer the only solution. less invasive procedures such as “valve-in-valve” TAVI offer modern and effective options to treat your deteriorating biological valve. Just like mechanical valve patients, it is critical for these patients to have good oral hygiene and use prophylactic antibiotics when necessary to prevent the risk of infection.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a biological heart valve?

Biological valves are derived from pig, bovine or human tissues. It is closer to the natural structure, but has a limited lifespan.

What is the difference between mechanical and biological valves?

Mechanical valves are more durable but require lifelong use of blood thinners. Biological valves have a shorter lifespan but usually do not require long-term medication.

Which type of heart valve lasts longer?

Mechanical valves usually last a lifetime. Biological valves function for 10-20 years.

Who gets a mechanical heart valve?

It is preferred for young patients, those without risk of reoperation and those who want long-term durability.

Who gets a biological heart valve?

It is preferred for women of advanced age, those at risk of taking blood thinners or women planning a pregnancy.

Does a mechanical lid make noise?

No, in the past some mechanical covers made noise, but nowadays double leaflet and cable-metal covered covers do not make noise.

Is heart valve surgery risky?

As with any surgery, there are risks, but the success rate is high with modern surgical techniques.

What happens if someone with a mechanical valve does not take blood thinners?

A clot may form on the valve. This can be life-threatening.

What to do if the biological valve fails over time?

The cover may need to be replaced.

How long does valve replacement surgery take?

It usually lasts between 2-4 hours, but may vary depending on the general condition of the patient.

How is quality of life affected after valve replacement?

After a successful surgery, the patient can breathe more easily, their effort capacity increases and their quality of life improves.

Can I do sports after this surgery?

Light and regular exercises can be done with the doctor’s approval. Heavy exercise should be avoided.

Which cover type is right for me?

The decision is made by the cardiac surgeon, taking into account factors such as age, health status, lifestyle and medication use.

Prof. Dr. Yavuz Beşoğul graduated from Erciyes University Faculty of Medicine in 1989 and completed his specialization in Cardiovascular Surgery in 1996. Between 1997 and 2012, he served at Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine as Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor, respectively. Prof. Dr. Beşoğul, one of the pioneers of minimally invasive cardiovascular surgery in Türkiye, has specialized in closed-heart surgeries, underarm heart valve surgery, beating-heart bypass, and peripheral vascular surgery. He worked at Florence Nightingale Kızıltoprak Hospital between 2012–2014, Medicana Çamlıca Hospital between 2014–2017, and İstinye University (Medical Park) Hospital between 2017–2023. With over 100 publications and one book chapter, Prof. Dr. Beşoğul has contributed significantly to the medical literature and is known for his minimally invasive approaches that prioritize patient safety and rapid recovery.