Kawasaki disease is an acute vasculitis affecting medium-sized arteries, primarily in children under five years old. It can cause coronary artery aneurysms if not diagnosed and treated early.

The disease typically presents with persistent fever, rash, conjunctivitis, swollen lymph nodes, and mucosal changes. Clinical criteria are crucial for accurate diagnosis.

Complications include myocarditis, arrhythmias, and vascular aneurysms. Regular cardiac evaluation is essential to detect and manage long-term sequelae in affected children.

Treatment primarily consists of intravenous immunoglobulin and high-dose aspirin therapy. Early intervention significantly reduces the risk of coronary artery involvement and improves outcomes.

| Definition | An acute vasculitis (inflammation of the veins) disease that affects medium-sized vessels and is characterized by fever and rash, especially in children under 5 years of age |

| Causes | Not known exactly; possibly genetic predisposition and infectious triggers are involved |

| Risk Factors | children under 5 years of age, children of Asian descent, male gender, familial predisposition |

| Symptoms | High fever (longer than 5 days), redness of the mouth and tongue (strawberry tongue), soreness and peeling of the hands and feet, dizziness, lymph node enlargement in the neck, redness of the eyes, cracking of the lips |

| Diagnostic Methods | Clinical findings, blood tests (CRP, sedimentation, leukocyte count), echocardiography, urinalysis |

| Treatment Methods | High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), aspirin, corticosteroid therapy when necessary, regular heart checks |

| Complications | Coronary artery aneurysms, myocarditis, heart failure, arrhythmia, valve diseases |

| Prevention Methods | There is no specific prevention method; early diagnosis and treatment can prevent complications |

What is Kawasaki Disease and what does it do in the body?

You can think of Kawasaki disease as a moment of confusion in which the body’s immune system attacks its own blood vessels. This is an inflammation of the blood vessels, called “vasculitis” in medical language. All small and medium-sized vessels in the body can be affected, but the main source of concern for us is the coronary arteries that supply the heart muscle.

The inflamed vessel wall swells, weakens and loses its elasticity. This weakened wall cannot withstand the pressure of the blood flowing through it and may balloon outward. We call these balloonings “aneurysms”. Think of it like a weak spot in a tire that balloons over time. These aneurysms can disrupt the blood flow, allow clots to form inside them or, very rarely, rupture. Even after the inflammation has healed, the vessel wall can remain hardened and narrowed (stenosis), like a scar, which narrows the bloodway to the heart.

The disease is also known as “mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome”. This name means that the disease affects not only the blood vessels, but also the wet surfaces (mucosa) such as the inside of the mouth, the eyes and the lymph nodes in the neck. This is why symptoms such as red eyes, chapped lips and a sore neck are often seen in children.

Why does Kawasaki Disease occur?

A clear answer to this question has still not been found after more than fifty years of research. But we do know that the disease is not caused by a single germ or virus, that it is not contagious. The strongest theory available is that it is like a three-piece jigsaw puzzle:

A Trigger Factor: The fact that the disease usually makes small outbreaks in winter and spring and begins with infection-like symptoms such as fever and rash suggests that a microbe or environmental agent initiated the process. However, no specific culprit has been found to date.

Genetic Predisposition: This factor explains why the disease is more common in some families, especially in children from East Asia, such as Japan. The genetic makeup of the child makes him or her more susceptible to this disease. Having a sibling with Kawasaki disease can increase the risk tenfold.

An Abnormal Immune Response: When a genetically predisposed child is confronted with that unknown trigger, the immune system displays a disproportionate use of force. Defense cells that should normally protect the body mistakenly attack their own blood vessels, causing inflammation. This is a temporary but very violent reaction of the dependency system.

What are the symptoms of Kawasaki Disease?

Kawasaki disease is diagnosed by a combination of certain clinical signs. It is therefore very important that you, as a parent, recognize these symptoms. In a classic Kawasaki case, your child will first have a persistent fever that lasts five days or more and does not respond well to standard fever reducers.

This fever is expected to be accompanied by at least four of the following symptoms:

- Heat and redness of the hands and feet.

- Peeling of the skin starting from the fingertips in the following weeks.

- Diffuse rash throughout the body, especially in the trunk and groin area.

- Leakless redness of the white part of the eyes.

- Bright redness, dryness and cracking of the lips.

- A bright red and purulent appearance of the tongue, called “strawberry tongue”.

- A painful lymph node enlargement the size of a walnut, usually occurring on one side of the neck.

The disease usually progresses in three phases. The first phase (acute phase) is the first 1-2 weeks, when the fever and other symptoms are most intense and the child is very restless. In the second phase (subacute phase), the fever subsides but the hands and feet begin to peel; the risk of developing aneurysms in the heart vessels is highest during this period. The third phase (recovery phase) is when symptoms disappear but it can take months for the body to recover.

An important point to remember is “atypical” or “incomplete” Kawasaki disease. Especially in infants younger than 1 year, all five of the above symptoms may not be present despite the presence of fever. Although this complicates the diagnosis, the risk of heart damage is just as serious. Therefore, in case of doubt, a physician should be consulted.

How is Kawasaki Disease diagnosed?

There is no specific blood test or X-ray for Kawasaki disease. The diagnosis is made by an experienced physician putting together clues like a detective. This is a “clinical diagnosis” process and involves several steps.

First of all, the doctor asks about the presence of the symptoms listed above. Details such as how many days the child’s fever has been going on, when the dizziness started, whether there is a change in the lips or eyes are very important. Sometimes some symptoms may come and go, so listen carefully to the story of the last week.

The second step is to rule out other diseases that can cause similar symptoms, i.e. to make a “differential diagnosis”. Some infections, rash or allergic reactions can mimic Kawasaki disease. Some simple tests can be ordered to understand this:

- Boaz culture

- Blood count

- Urinalysis

Finally, there are some blood tests that support the diagnosis. Although these tests are not specific to the disease, they strengthen the diagnosis by showing that there is a serious inflammation in the body. These tests usually show the following findings:

- Significant elevation in CRP (C-reactive protein).

- Significant increase in ESR (sedimentation rate).

- Increase in white blood cells (leukocytes).

- Excessive increase in blood platelets from the second week of the disease.

- Slight elevation of liver enzymes.

What methods are used to see the effects of Kawasaki Disease on the heart?

The most insidious aspect of Kawasaki disease is the risk of heart damage that is not visible from the outside. Therefore, imaging the heart and coronary arteries is the most critical part of diagnosis and treatment. The most important and basic method used for this purpose is echocardiography, or “echo” as it is commonly known.

Echocardiography is a painless, harmless and radiation-free ultrasound method that uses sound waves to take a moving movie of the heart and its blood vessels. It does not cause any discomfort to your child. Eko’s role in this process is multifaceted.

At the time of diagnosis, a baseline echo is performed to see the condition of the heart at that moment. It is measured whether the heart muscle (myocardium) is affected by inflammation, whether there is a leak in the heart valves and, most importantly, the diameter of the coronary arteries. Instead of simply measuring the vessel diameter in millimeters, a special calculation called the “Z-score” is used here. The Z-score adjusts the measured vessel diameter to the child’s height and weight. This way, it can be objectively determined whether the vein is really wide according to the child’s body structure.

Once treatment has started, the echo is usually repeated after 1-2 weeks and 4-6 weeks. These follow-up echoes are vital to monitor whether the treatment is working and, more importantly, whether the coronary arteries are dilating or developing an aneurysm over time.

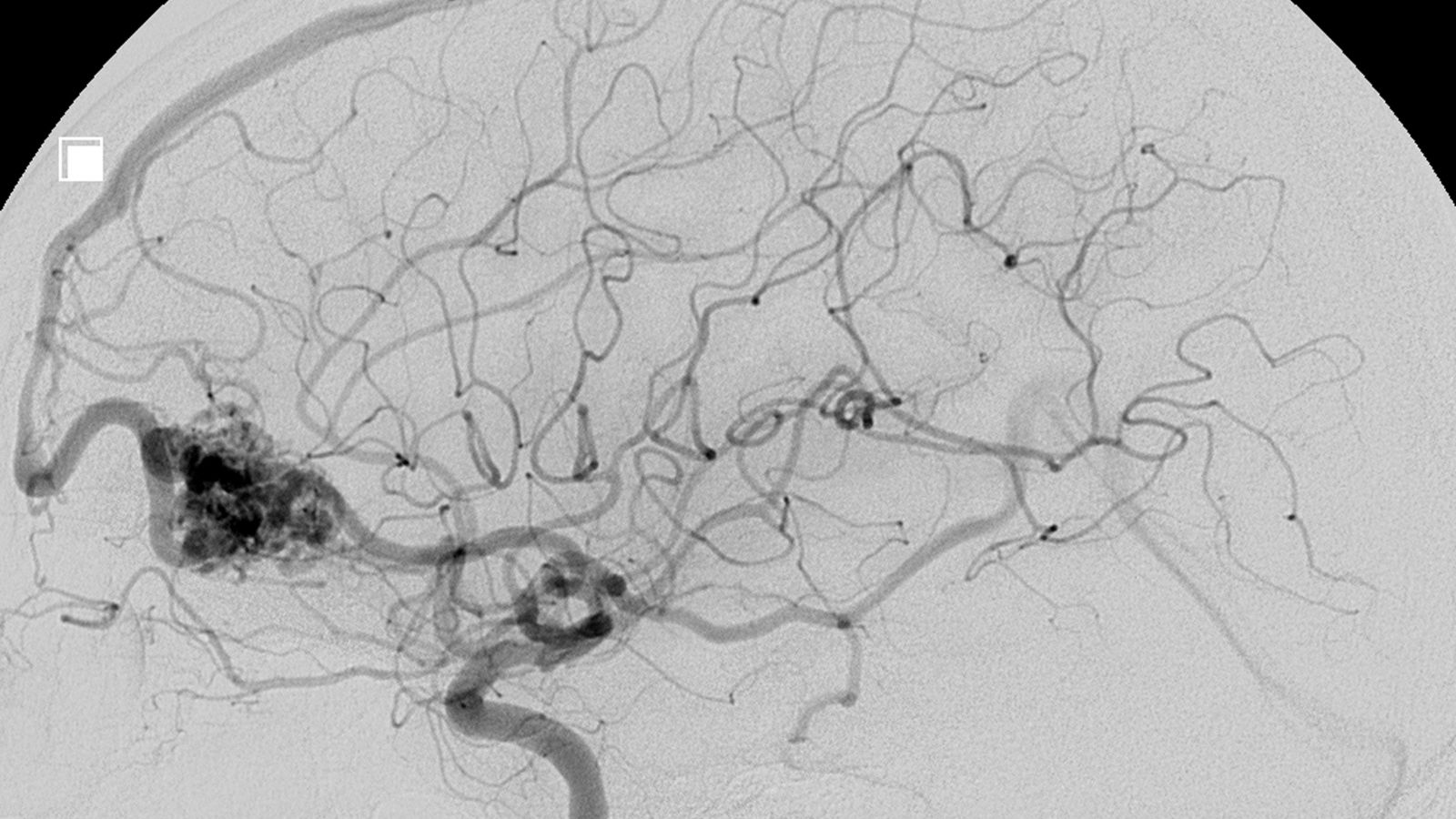

In some special cases, when the echo does not give a clear image or more detailed examination is required, more advanced imaging methods such as Computed Tomography (CT) Angiography or Magnetic Resonance (MR) Angiography may be used.

How is Kawasaki Disease treated?

Treatment of Kawasaki disease is a matter of urgency and has two main goals: to suppress the severe inflammatory flare-up in the body and to prevent permanent heart damage. The success of treatment depends very much on timing, i.e. starting it within the first 10 days of illness. Standard treatment consists of two main inpatient medicines.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG): This is the backbone of treatment. IVIG is a serum containing concentrated antibodies derived from the blood of thousands of healthy blood donors. It is given intravenously, usually as a single high-dose infusion lasting 8-12 hours. IVIG calms the body’s overworked immune system and stops the attack on blood vessels. IVIG treatment has the miraculous effect of reducing the risk of developing an aneurysm in the heart vessels from % to less than 5%.

Aspirin Aspirin is used for two different purposes in treatment. At the beginning of treatment, it is given in high doses with IVIG to suppress inflammation and reduce fever. After the child’s fever returns to normal, the dose is significantly reduced. The aim of this low-dose aspirin is no longer to suppress inflammation, but to prevent blood platelets (platelets) from sticking to the inflamed and purulent vessel walls and forming clots. This low-dose treatment is usually stopped after 6-8 weeks if no problems with the heart vessels are detected.

What happens if there is no response to treatment for Kawasaki disease?

About -20% of children with Kawasaki disease may not respond as expected to standard IVIG treatment. We call this “IVIG resistance” and it is indicated by the failure or resumption of fever within 36 hours of treatment. This is a sign of a more stubborn and aggressive course of the disease and means a higher risk of cardiac complications.

Fortunately, there is a “Plan B” and even a “Plan C” ready for such situations. In case of resistance, physicians take a gradual approach and switch to stronger treatments.

These second-line treatment options include the following:

- A second dose of IVIG infusion.

- Corticosteroids (strong forms of medication, commonly known as cortisone, given in high doses intravenously).

- Biological agents such as Infliximab (these are special drugs that target and inactivate key molecules in the inflammatory process).

In very rare and persistent cases that do not respond to these treatments, more powerful immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporine or plasmapheresis (the process of clearing the inflamed plasma part of the blood) may be used. This stepwise approach ensures that each child receives the most appropriate and effective treatment according to their needs.

What is the long-term health of a child with Kawasaki Disease?

The future health of a child with Kawasaki disease depends on whether the disease leaves a permanent scar on the heart. Fortunately, the vast majority of children who receive timely and correct treatment, about one in ten, recover completely without any heart problems. The long-term health prospects of these children are no different from those of other children who have never had the disease.

However, a small number, especially those with giant aneurysms, require lifelong cardiologic follow-up. The possible long-term risks for these patients are as follows:

- Stenosis (Stenosis): Over the years, the wall in the area of the vessel with an aneurysm can thicken and narrow, blocking blood flow to the heart.

- Thrombosis (clotting): The slow blood flow inside the aneurysm sac creates a favorable environment for clots to form. These clots can block a blood vessel and cause a heart attack.

Because of these risks, children with permanent aneurysms take low-dose aspirin for life. Those with giant aneurysms are additionally given stronger blood thinners (anticoagulants) to prevent clotting. These children are followed up with tests such as regular echo, ECG, stress test and, if necessary, CT/MR angiography, which are determined according to their risk level.

Is surgery necessary if serious problems develop in the heart vessels after Kawasaki Disease?

Yes, in some cases surgery is necessary and can be life-saving. Surgery is not to repair the disease itself, but the structural problems it leaves behind – the “plumbing problems”. This decision is made by an experienced cardiology and cardiovascular surgery team after a detailed assessment of the patient’s condition.

The main situations where surgical intervention is necessary are:

- The development of a severe stenosis that prevents adequate blood supply to the heart muscle despite drug treatment.

- Chest pain with exercise (angina) or a silent blood supply disorder (ischemia) detected on a stress test.

- The formation of a clot in the aneurysm despite blood thinners or blockage of the vessel by a clot.

- The presence of giant aneurysms (larger than 8 mm in diameter) with very high future risks.

What surgeries are performed for complications of Kawasaki Disease?

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is the main surgical procedure to solve the serious coronary artery problems associated with Kawasaki disease. We can liken this surgery to building a “side road” or “viaduct” on a blocked highway.

During surgery, the surgeon removes a healthy piece of blood vessel from another part of the body. In children and young people, arteries from inside the chest wall (internal mammary artery – IMA) are usually preferred because of their long life span. This healthy vessel (graft) is sutured to the area of the healthy vessel beyond the obstruction or stenosis. The blood thus bypasses the occlusion zone and reaches the heart muscle via this new pathway, restoring the heart’s nutrition.

In some cases, especially with giant aneurysms that can be a source of clots, bypass alone is not enough. The aneurysm sac may also need to be surgically removed (resection) or closed off to blood flow (ligation). These procedures are also performed together with bypass surgery.

Why is it important to follow young people with Kawasaki Disease into adulthood?

Thanks to effective treatments, Kawasaki disease is no longer a fatal disease, but a chronic condition that must be managed. Children who survive this disease with cardiac complications now grow up healthy and reach adulthood. This has created a new and important responsibility for the medical profession: to ensure that these young people “graduate” smoothly from pediatricians (pediatric cardiology) to adult cardiologists (adult cardiology).

This “cycle of care” is of vital importance. Young adulthood is a time when education, career and social life take precedence and regular medical check-ups can be neglected. This neglect can mean a silent danger, especially for a young person with a problem such as a heart aneurysm.

It is therefore essential that this transition takes place in a planned and structured program. The aim of this process is to teach the young person about his/her own illness, the medicines he/she is taking, the risks involved and to give him/her the awareness to take responsibility for his/her own health. A successful transition, through the coordinated work of pediatric and adult cardiology teams, ensures that these young people remain healthy and safe for life.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Kawasaki disease?

Kawasaki disease is an inflammatory disease, usually affecting children, that affects the medium-diameter vessels and can lead to heart complications.

Who does it occur in?

It is most common in children under 5 years of age, especially between 6 months and 4 years. It is more common in boys.

What are the symptoms?

The main symptoms are high fever, redness of the mouth and lips, dizziness, reddening of the eyes, heat in the hands and feet, and enlarged lymph nodes in the neck.

Is Kawasaki disease contagious?

No, Kawasaki disease is not contagious.

Why does it happen?

The exact cause is unknown, but genetic predisposition and overreaction of the immune system may play a role.

Is it a dangerous disease?

Yes, especially when left untreated, it can affect the heart vessels and lead to serious complications.

How does it affect the heart?

It can cause enlargement of the heart vessels (coronary arteries), aneurysms and, rarely, the risk of heart attack.

How is the diagnosis made?

Diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms and blood tests. ECHO (echocardiography) is performed to see if the heart is affected.

How is it treated?

Treatment usually involves intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and aspirin. Cortisone treatment can be added if necessary.

How long does treatment take?

In the acute phase, IVIG treatment lasts for several days. Aspirin treatment can take weeks or months.

Does it leave permanent damage?

With early treatment, most children do not develop permanent damage. However, those who develop problems in the heart vessels need long-term follow-up.

Which branchÅ deals with?

It should be followed up by specialists in pediatric cardiology and pediatric infectious diseases.

Is a fever considered to have passed?

No, even if the fever goes down, cardiac complications can develop and must be monitored.

Does Kawasaki disease recur?

Although rare, it may recur. Children with a story should therefore be closely monitored.

Can my child return to normal life after Kawasaki disease?

Yes, if treatment and follow-up are successful, children usually go on to lead healthy normal lives.

Prof. Dr. Yavuz Beşoğul graduated from Erciyes University Faculty of Medicine in 1989 and completed his specialization in Cardiovascular Surgery in 1996. Between 1997 and 2012, he served at Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine as Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor, respectively. Prof. Dr. Beşoğul, one of the pioneers of minimally invasive cardiovascular surgery in Türkiye, has specialized in closed-heart surgeries, underarm heart valve surgery, beating-heart bypass, and peripheral vascular surgery. He worked at Florence Nightingale Kızıltoprak Hospital between 2012–2014, Medicana Çamlıca Hospital between 2014–2017, and İstinye University (Medical Park) Hospital between 2017–2023. With over 100 publications and one book chapter, Prof. Dr. Beşoğul has contributed significantly to the medical literature and is known for his minimally invasive approaches that prioritize patient safety and rapid recovery.