Heart diseases in athletes are often associated with structural or electrical abnormalities that may remain unnoticed during routine training. These conditions can increase the risk of sudden cardiac events, making early diagnosis and prevention essential.

Common heart problems in athletes include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, coronary anomalies, and myocarditis. Such conditions may cause chest pain, fainting, or palpitations, especially during intense physical exertion.

Preventive screening in athletes focuses on electrocardiograms, echocardiography, and stress tests. Early detection helps reduce the likelihood of life-threatening incidents and supports safer athletic performance.

Treatment of heart diseases in athletes depends on the underlying condition. Management may include medication, lifestyle adjustments, or in some cases surgical intervention, while ensuring the athlete’s ability to continue sports safely when appropriate.

What is Athlete’s Heart Syndrome and Why is it Important?

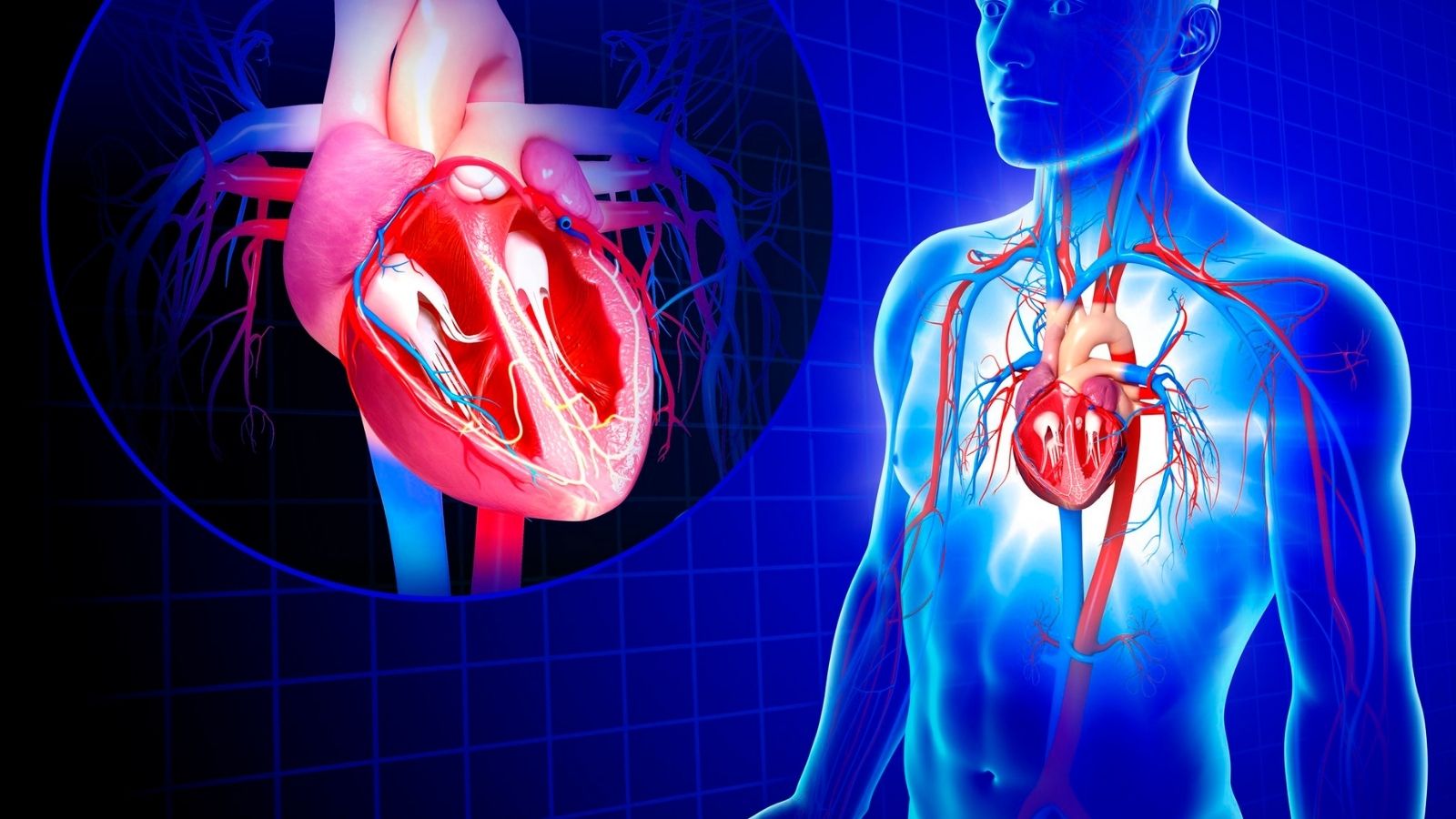

Athlete’s Heart Syndrome, in its simplest definition, is a set of structural and functional changes that the heart of an individual who trains regularly and intensively undergoes to meet the increased demands. Although it is called a syndrome, it is not a disease. On the contrary, it is a natural, expected and healthy response of the heart to the body’s increased demand for blood and oxygen during exercise. This adaptation process is most pronounced in endurance sports such as long-distance running, cycling, rowing and swimming.

So, if this is a healthy change, what do we have to worry about? The problem comes from a dilemma created by this adaptation. On the one hand, the athlete’s heart is a sign of superior fitness and performance, but on the other hand it can mimic the symptoms of serious heart disease. This physiological growth and electrical changes in the heart can be confused with pathological findings seen in conditions such as Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM), a genetic disease of the heart muscle. This confusion can lead to a healthy athlete being mistaken for a sick athlete, or worse, a real heart patient being overlooked as having an “athlete’s heart”. This is why understanding the athlete’s heart and differentiating it from pathological conditions is the most critical step in athlete health management.

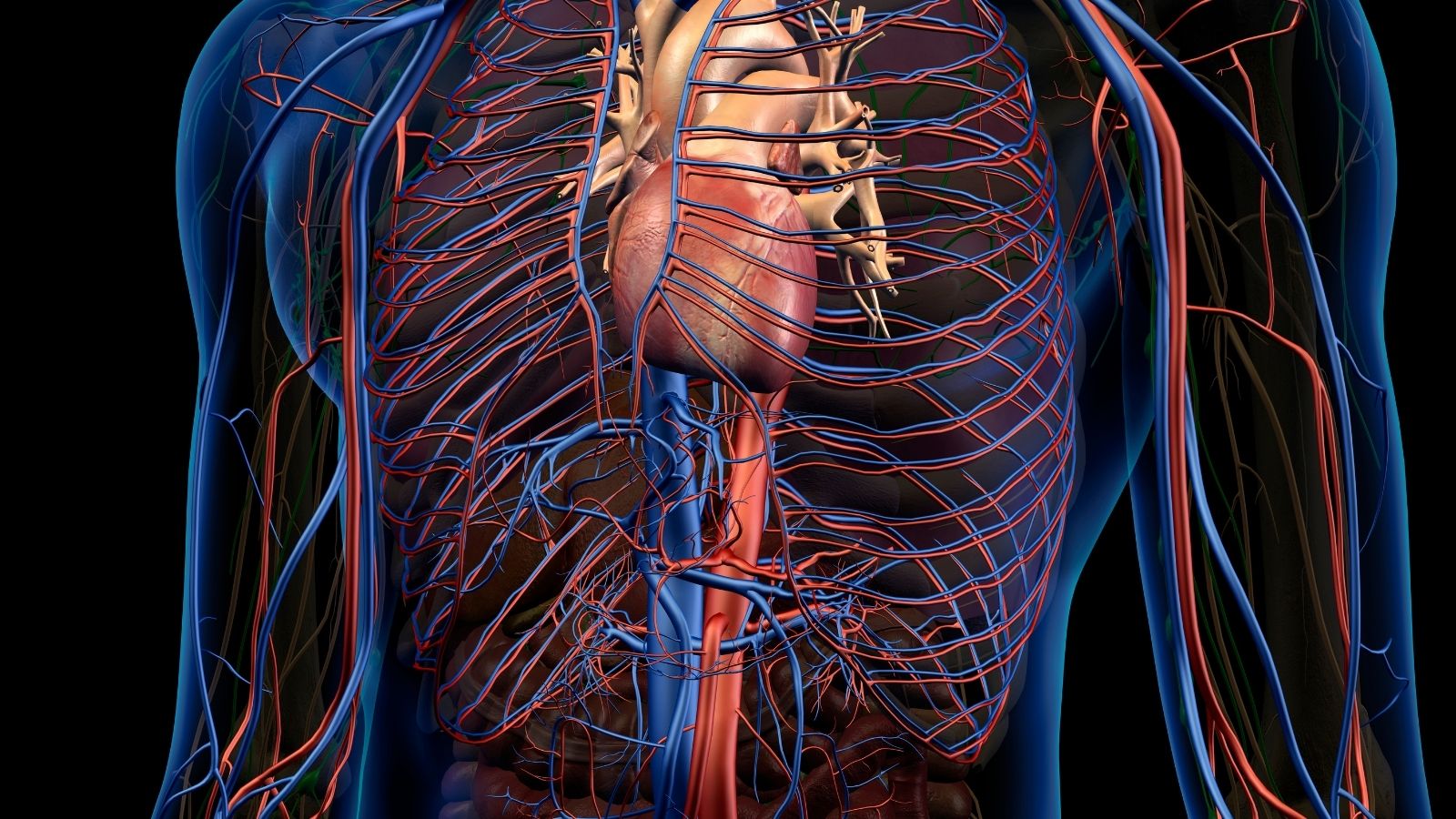

What Structural Changes Are Observed in the Athlete’s Heart?

To adapt to the increased workload, the heart muscle responds just like any other muscle by growing bigger and stronger. Two main structural changes occur during this process: The heart chambers enlarge and the heart walls thicken. The type of sport practiced determines the character of this change.

- Endurance Sports: In sports such as running, the heart has to pump high volumes of blood continuously. In response to this “volume load”, the heart chambers dilate markedly and the wall thickness increases in a balanced manner proportional to this expansion.

- Power Sports: In sports such as weightlifting, the heart is tasked with pumping blood against very high pressure for short periods of time. This “pressure load” causes the walls to thicken more significantly, without the heart chambers becoming too large.

- Mixed Sports: Many sports today, such as cycling, rowing or soccer, involve both endurance and strength components. Therefore, these athletes show a mixed remodeling that combines characteristics of both types of adaptation.

These structural changes are expected to remain within physiological limits. For example, the left ventricular wall thickness measured by echocardiography in a male athlete usually does not exceed 13 millimeters and rarely reaches 15-16 millimeters. Significantly exceeding these limits raises the suspicion of an underlying heart disease and requires a detailed examination.

What are the Functional and Electrical Adaptations of the Athlete’s Heart?

Structural remodeling of the heart is accompanied by important functional and electrical adaptations that optimize its performance. These changes are the basis for the athlete’s high effort capacity.

The most basic functional adaptation is an increase in the amount of blood the heart pumps through the body with each beat, the “stroke volume”. This increased efficiency allows the heart to save energy by working less at rest. The clearest indicator of this is the low resting heart rate (bradycardia) that we often see in athletes. In athletes, the resting heart rate can drop to below 40 beats per minute, or even as low as 30 in some elite athletes. This indicates that the heart is working more economically and has a larger heart rate reserve for exercise.

These adaptations lead to a series of characteristic changes in the electrocardiogram (ECG), which records the electrical activity of the heart. Most of these findings are considered benign. However, a critical distinction must be made here. These performance-enhancing adaptations themselves can make the heart more vulnerable to certain rhythm disturbances (arrhythmias). For example, enlarged heart chambers, especially the atria, can be a favorable breeding ground for the development of a common rhythm disorder such as “atrial fibrillation”. It is therefore crucial to distinguish where physiological adaptation ends and potential risk begins.

What is the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death in Athletes?

The sudden death of a young and seemingly healthy athlete on the field is a tragic event that causes deep sadness and shock in the community. While these cases receive extensive media coverage, leading to an overestimation of the risk, scientific evidence shows that sudden cardiac death (SCD) in athletes is a rare event. Methodologically sound studies suggest that the risk in young athletes is approximately 1:40,000 to 1:80,000.

Although these figures show that the event is rare, it does not mean that the risk is insignificant, as each case is a family tragedy. Moreover, the risk is not equal for all athletes. There are some important factors that affect risk:

- Male athletes

- athletes over 35 years old

- Specific ethnicities (e.g. black athletes in the USA)

- High intensity and competitive sports

Especially in athletes over 35 years of age, the risk increases significantly compared to younger athletes. This is due to underlying causes that change with age.

What Are the Most Common Causes of Sudden Death in Young Athletes (<35 Years)?

When the heart of an athlete under the age of thirty-five suddenly stops beating, triggered by intense exercise, it is almost always due to a hidden congenital or genetic (inherited) heart abnormality. These diseases are often insidious and the athlete may be unaware of their condition until they experience a fatal event. The main structural and electrical heart diseases leading to sudden death in young athletes are

- Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM)

- Abnormal Coronary Artery Outlets

- Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (ARVC/ACM)

- Primary Electrical Diseases (Ion Channelopathies)

- Myocarditis (Heart Muscle Inflammation)

- Aortic Tears (in cases such as Marfan Syndrome)

In recent studies, autopsies of a significant proportion of young athletes with sudden cardiac death have failed to reveal a significant structural heart disease. This suggests that the underlying cause may be “channelopathies” affecting only the electrical system of the heart, which cannot be detected by autopsy.

What is the Main Cause of Sudden Death in Older Athletes (>35 Years)?

In contrast to young athletes, the risk profile completely changes in “master” or “veteran” athletes who are over 35 years of age and continue to actively participate in sports. In this age group, instead of rare genetic diseases, atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD), which is common in the general population and increases in frequency with age, comes to the fore. CAD is a narrowing or blockage of the arteries that feed the heart, caused by the build-up of plaques made of cholesterol and other substances on the walls of the arteries.

There is a confusing situation here: While regular exercise is one of the strongest protective factors against the development of CAD, CAD is also the number one cause of sudden death in older athletes. This is because, in the presence of silent CAD, intense exercise can tear a vulnerable plaque in the vessel wall, leading to sudden clot formation. This can trigger a heart attack or a fatal arrhythmia. This fact indicates that being physically fit does not mean being exempt from coronary artery disease and that the focus of cardiovascular screening for athletes in this age group should be to assess the risk of CAD.

What Warning Signs Can Precede Sudden Cardiac Death?

Although sudden cardiac death is often described as an unexpected event, in a significant proportion of cases, the body signals ahead of time. Research shows that around one-third of athletes who suffer an ACE experience warning signs in the weeks or months before the event. Recognizing these signs and taking them seriously can offer a vital opportunity to prevent a potential tragedy.

The main warning signs (prodromal symptoms) that an athlete, coach or family should never ignore are the following:

- Chest pain or discomfort due to exercise

- Unexplained fainting (syncope) or feeling like fainting

- Excessive and unexplained shortness of breath relative to performance level

- Unexpected and excessive fatigue

- Palpitations or irregular heartbeat

Sports culture’s indoctrination to “endure the pain” and “push your limits” can lead athletes to dismiss these symptoms as deconditioning or normal fatigue. The message is clear: These symptoms should never be considered normal, especially when they are new, more severe than expected or differ from the athlete’s usual condition.

How to Differentiate Athlete’s Heart from Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM)

HCM is a genetic disorder in which the heart muscle thickens abnormally and is one of the most common causes of sudden death in young athletes. Since the athlete’s heart also shows a physiologic thickening of the wall, it is vital to distinguish between these two conditions. This distinction requires a holistic assessment based on a set of criteria, not a single measure.

There are basic clues used to distinguish between the two situations:

- Heart Cavity Size: This is the most important distinguishing feature. In the athlete’s heart, the left ventricular cavity is enlarged to accommodate the increased blood volume. In HCM, it is usually normal or small because the thickened muscles narrow the cavity.

- Wall Thickness and Symmetry: In the athlete’s heart, thickening is usually symmetrical and less than 15 mm. In HCM, it is typically asymmetrical and often exceeds 15 mm.

- Relaxation Ability of the Heart: In the athlete’s heart, the relaxation function that allows the heart to fill with blood is normal or even increased. In HCM, the thick and hardened heart muscle cannot relax properly and this function is impaired.

- Detraining Test: In “gray zone” cases where the diagnosis remains unclear, the athlete is asked to stop training for 3-6 months. At the end of this period, the physiologic thickening due to the athlete’s heart regresses, while the pathologic thickening due to HCM persists.

- Advanced Imaging (Cardiac MRI): While cardiac MRI can show scar tissue (fibrosis) within the heart muscle in patients with HCM, this finding is not expected in the athlete’s heart.

Why Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (ACM) is Especially Dangerous for Athletes

Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (ACM) is an inherited disease caused by a genetic defect in the “glue” proteins that bind heart muscle cells together. When this “glue” is weak, the connections between heart muscle cells break down and are replaced over time by fat and scar tissue. This abnormal tissue sets the stage for life-threatening rhythm disturbances.

The particular risk of ACM for athletes is due to a unique gene-environment interaction: Exercise is not only a trigger for this disease, but also a factor that accelerates its progression. The mechanical stress of intense exercise causes these genetically weak heart muscle connections to deteriorate faster, leading to an earlier, more severe onset of the disease. Athletes diagnosed with ACM or known to carry the gene for the disease are therefore strongly advised to avoid competitive and high-intensity sports.

How to Differentiate Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) from Physiologic Heart Enlargement

Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a disease of the heart muscle in which the left ventricle, the main pumping chamber of the heart, becomes enlarged and has reduced contractile strength. These two conditions can be confused, as elite endurance athletes can also have a marked enlargement of the heart chambers due to training. In this “gray zone”, measurements at rest can be misleading to reach the correct diagnosis. The most valuable test for differentiation is exercise stress echocardiography, which assesses the functional reserve of the heart, i.e. its response to stress.

During the test, the contractile function of the heart is continuously monitored by ultrasound while the athlete exercises. A healthy athlete’s heart has a large functional reserve and increases its contractile strength markedly with exercise. A pathologically remodeled DCM heart, on the other hand, has a limited functional reserve. During exercise, the contractile force increases little or not at all, and in some cases may even decrease. Two hearts that look very similar at rest reveal their true nature when exposed to stress: One responds by becoming stronger, the other by becoming weaker. This functional difference is the key to reaching the correct diagnosis.

Why should cardiac screening be performed for athletes?

The most effective way to minimize the risk of sudden cardiac death in athletes is to detect underlying occult heart disease while the athlete is still healthy and asymptomatic. This is the main objective of cardiovascular screening, the most critical component of the health assessment prior to participation in competitive sports. Through early detection, preventive measures can be taken according to the athlete’s risk level. These measures can include banning the athlete from certain sports, starting medication or implanting implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) devices that can stop life-threatening arrhythmias. This protects the athlete’s health and prevents a potential tragedy.

What is the Importance of Using Electrocardiography (ECG) in Athlete Screening?

Electrocardiography (ECG) is a simple, inexpensive and harmless test that records the electrical activity of the heart. The vast majority of diseases associated with sudden cardiac death lead to abnormal findings on ECG. Therefore, the role of ECG in athlete screening is one of the most important topics in sports cardiology. There are two main approaches to this issue:

- American Approach (AHA/ACC): Discourages routine ECG screening due to concerns about high false-positive rates. It recommends ECG for athletes with a suspicious finding on physical examination and history.

- European Approach (ESC) and International Olympic Committee (IOC): Recommends routine ECG as part of pre-participation screening for all young and competitive athletes. The strongest basis for this approach is the data showing that the mandatory ECG screening program introduced in Italy in 1982 significantly reduced sudden cardiac death rates in athletes.

The main difference between these two approaches is who interprets the ECG rather than the ECG itself. Normal ECG changes specific to the athlete’s heart can easily be interpreted as pathologic by a physician who is not experienced in this field. However, thanks to the “International Criteria” developed in the last decade, which take into account changes specific to the athlete’s heart, the false alarm rate of the ECG has been reduced to less than 3% without losing its power to detect diseases. This shows that the ECG is a powerful screening tool that, in the right hands, i.e. when interpreted by an expert familiar with the latest international criteria, can detect the largest number of at-risk athletes with the fewest false alarms.

According to which criteria should an athlete’s ECG be interpreted?

Correctly interpreting an athlete’s ECG requires special expertise. International standards developed for this purpose provide a clear roadmap for physicians by classifying ECG findings into three main groups.

Normal ECG Findings (Physiologic Changes Due to Training): These findings are normal responses of a healthy heart to intense training and do not require further investigation:

- Sinus bradycardia (low heart rate)

- Sinus arrhythmia (change in heart rate with breathing)

- First degree AV block (slight slowing of conduction)

- Early repolarization pattern

- Isolated voltage criteria consistent with heart enlargement

- Incomplete right bundle branch block

Borderline ECG Findings (Borderline): Individually, they usually do not indicate pathology, but if more than one is present or there is clinical suspicion, further investigation may be considered:

- Left axle deviation

- Right axle deviation

- Criteria for left or right atrial dilatation

- Complete right bundle branch block

Abnormal ECG Findings (that require further investigation): These findings are not related to training and may be a sign of serious underlying heart disease. The presence of any of these should be investigated by a specialist physician with further tests:

- T wave negativity in certain regions

- ST segment collapse

- Pathologic Q waves

- Complete left bundle branch block

- Ventricular pre-excitation (WPW pattern)

- Significant long QT interval

- Brugada Type 1 pattern

- Advanced heart blocks

- Serious rhythm disturbances (such as ventricular tachycardia)

What is the Role of Echocardiography (ECHO) in Athlete Evaluation?

When screening methods such as history, physical examination and ECG raise suspicion of a risk or abnormality, the next and most important step is usually transthoracic echocardiography (ECHO). ECHO is an ultrasound method that uses sound waves to create live, moving images of the heart. Its main role in sports cardiology is to eliminate uncertainties and reach a definitive diagnosis. ECHO is the most critical tool in solving the “gray zone” problem, i.e. distinguishing physiological adaptations of the athlete’s heart from pathological conditions such as Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) or Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM). It provides a definitive diagnosis by precisely measuring heart wall thickness, cavity dimensions, valve structure and contraction-relaxation functions of the heart.

What should be the treatment approach in athletes diagnosed with heart disease?

When an athlete is diagnosed with heart disease, it is a major turning point for both their health and their career. In the past, such diagnoses often meant the end of a sporting life. Today, however, the approach in sports cardiology has evolved from strict prohibitions to individualized risk assessment and “Shared Decision-Making”. This modern model establishes a partnership between the physician and the athlete: The physician’s task is to analyze the athlete’s individual risk profile in detail, using the best available scientific evidence, and to present all information transparently to the athlete. The athlete, in turn, actively participates in the decision process, combining this comprehensive information with his or her values, goals and risk tolerance. The goal is not always to ban sports in the name of absolute safety, but to keep the athlete in the activity they love in the safest way possible by developing strategies to minimize risk.

Is it Possible to Return to Sports with Surgical Treatment in Some Heart Diseases?

Yes, it is absolutely possible. Surgical treatment for certain structural heart diseases can not only relieve symptoms but also correct the underlying anatomical problem, eliminating the risk of sudden death and allowing the athlete to return to sport safely.

- Septal Myectomy (for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy): Surgical removal of part of the thickened septal muscle that blocks blood flow in obstructive HCM. This open-heart surgery immediately and permanently improves symptoms, significantly reduces the risk of sudden death and can open the door to a return to sport. It is considered the “gold standard” treatment in experienced centers.

- Abnormal Coronary Artery Repair: Surgical correction of abnormal coronary arteries, which can compress during exercise and cause sudden death, aims to eliminate this fatal risk. The most commonly used “unroofing” technique permanently prevents the artery from being compressed. This surgery can save the athlete’s life and allow them to continue playing sports safely.

These surgical interventions are life-changing treatments that take an athlete from thinking “I have a disease that is keeping me out of sport” to “I have a fixable problem and surgery could be the key to getting back in the game”.

When Can an Athlete with Myocarditis Safely Return to Sport?

An athlete diagnosed with myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) should strictly avoid sports during the acute phase, as the heart muscle is very sensitive and fragile. Intense exercise during this period can increase inflammation and trigger life-threatening arrhythmias. A safe return to sport usually requires at least 3 to 6 months of rest followed by a thorough cardiac evaluation. This assessment should verify that all of the following criteria are met:

- Complete normalization of heart function (LVEF on ECHO)

- Improvement of inflammation markers in blood tests

- absence of severe arrhythmias on 24-hour Holter and effort test

A return to sport is not safe unless these criteria are met.

Can Athletes with a Pacemaker or ICD Exercise?

Yes, athletes with a pacemaker or ICD (implantable cardioverter-defibrillator) are generally encouraged to exercise. However, the decision to participate in sport should be made on an individual basis. The most important factor in the decision is the underlying heart disease that requires the device, rather than the device itself. The impact of sport on this disease is the primary determinant. Although an ICD provides protection against sudden death, it should not be seen as a “ticket back to sport”. Sports with a high risk of collision and contact (soccer, ice hockey, combat sports, etc.) are generally not recommended due to the risk of damage to the device or electrodes. The final decision should be made in an individualized approach where the risks and benefits are carefully weighed, the athlete is informed and closely monitored by a specialist physician.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is athlete’s heart syndrome?

It is the occurrence of structural changes such as thickening of the heart muscle and enlargement of the heart chambers in people who exercise intensely and for a long time.

Is athlete’s heart a disease?

No, it is a physiological adaptation. However, it needs to be differentiated from pathological heart disease.

How to distinguish athlete’s heart from heart disease?

Evaluation is performed with detailed ECG, echocardiography and, if necessary, cardiac MRI.

What are the most common heart diseases in athletes?

Genetic rhythm disorders, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia and valvular heart disease may be seen.

What causes sudden cardiac death in athletes?

Often undiagnosed underlying heart diseases can cause sudden rhythm disturbances and sudden death.

Does intense exercise damage the heart?

Excessive exercise without proper supervision and monitoring can lead to structural changes in the heart and arrhythmias.

Are ECG differences normal in athletes?

Yes, some changes in ECG are considered normal in trained individuals. However, every finding should be evaluated.

Is a heart check necessary before playing sports?

Evaluation with CT coronary angiography or nuclear myocardial scintigraphy is recommended, especially for individuals who will engage in professional or intensive sports.

Can a person with an athlete’s heart develop a disease?

Yes, not all athletes have heart disease, but if there are associated risk factors, further evaluation may be necessary.

Which symptoms may indicate heart disease?

Symptoms such as chest pain, fainting, palpitations and shortness of breath during exercise should be taken seriously.

Does the athlete’s heart develop the same in men and women?

Although the general principles are similar, they may be more pronounced in men due to hormonal differences.

Does the athlete’s heart fade over time?

Structural changes in the heart may regress over time when active sport is discontinued.

Can athletes with heart disease exercise?

Light and controlled exercise may be recommended depending on the condition. However, it should not be done without a doctor’s permission.

Should young athletes have heart screening?

Yes, screening tests are important for early detection of possible heart problems in young people who play sports.

Prof. Dr. Yavuz Beşoğul graduated from Erciyes University Faculty of Medicine in 1989 and completed his specialization in Cardiovascular Surgery in 1996. Between 1997 and 2012, he served at Eskişehir Osmangazi University Faculty of Medicine as Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor, respectively. Prof. Dr. Beşoğul, one of the pioneers of minimally invasive cardiovascular surgery in Türkiye, has specialized in closed-heart surgeries, underarm heart valve surgery, beating-heart bypass, and peripheral vascular surgery. He worked at Florence Nightingale Kızıltoprak Hospital between 2012–2014, Medicana Çamlıca Hospital between 2014–2017, and İstinye University (Medical Park) Hospital between 2017–2023. With over 100 publications and one book chapter, Prof. Dr. Beşoğul has contributed significantly to the medical literature and is known for his minimally invasive approaches that prioritize patient safety and rapid recovery.